PROFILES | By Mark Lewis

Full Circle

Burned out of Ventura by the Thomas Fire, the distinguished artist Gerd Koch is back in Ojai, where his career began.

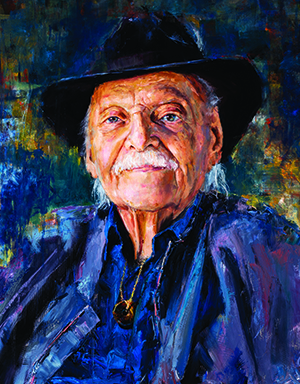

Gerd Koch portrait by Duane Eells

The street sign says Shippee Lane, but it’s memory lane for Gerd Koch as his self-appointed chauffeur (yours truly) turns right off Thacher Road and drives south on Shippee toward Koch’s former home, the place where he first found himself as an artist.

That was back in the mid 1950s, when young Gerd, and his then wife and fellow artist Irene Koch, were still relatively new to Ojai. They bought two acres of undeveloped East End chaparral and built themselves a one-room house that doubled as their studio, although Gerd preferred to set up his easel outdoors.

His abstract-expressionist Ojai landscapes soon made a splash in Los Angeles, but he maintained his home base in Ojai until 1969, when he moved down the road to teach art at Ventura College. Then, last December, the devastating Thomas Fire destroyed the home Koch shared with his longtime partner, the distinguished painter Carole Milton. As a result, they have relocated to a rented house in Ojai, where her daughter lives. And so, after almost 50 years in Ventura, Gerd Koch at 89 is back in the community where he started out.

“Everything looks different,” he says, as we turn left from Shippee onto Calle Moreno, which dead-ends in the vicinity of Koch’s former property. Different how? Well, in Gerd’s day, Calle Moreno was unpaved and his was the only house on it. Nowadays it’s a smooth stretch of asphalt lined with houses, none of which appears to be the one he erected there six decades ago.

Koch is giving me a tour of his Ojai, or what’s left of it — the valley as he knew it in the ‘50s and ‘60s. “It was very bohemian,” he says. “Then it became very hippy.”

He has a story to offer for almost every building we pass, usually involving an art exhibit or event that he had shoehorned into some unlikely space.

“That’s where I gave my puppet show,” he exclaims as we pass the library.

Our tour ends where Koch’s tenure in Ojai began, on Tree Ranch Road in the Upper Valley. This was the site of his first Ojai address, before Calle Moreno. It was December 1952 when Gerd and Irene and their friend Ray Foster arrived in the Upper Valley and announced plans to start an art commune. Gerd was just 23 and utterly unknown in the art world, and Tree Ranch Road was a long way off the beaten path – yet somehow this announcement made news in Los Angeles.

“Community Project: Ranch Center Planned For Artists, Actors and Writers,” the Los Angeles Times reported in January 1953. “Three artists now form the nucleus of a group they hope will some day contain 10 members, all of them painters, poets, actors or photographers. They plan to incorporate and establish the community as much as possible on a self-sufficient basis.”

The commune did not last long, but the Kochs stayed on, having decided that Ojai would serve admirably as both their home and their muse.

Born and raised in Detroit, Koch graduated from Michigan’s Wayne State University in 1951, armed with an art degree and a determination to put it to use by becoming a painter. This was the great age of abstract expressionism, and Koch embraced the ascendant style. But, instead of heading east to Greenwich Village and hanging out in the Cedar Tavern with Willem de Kooning and Jackson Pollack, Koch headed west to Southern California in search of a rural idyll. He brought along his new bride, Irene, a fellow art major at Wayne State. They ended up in Santa Barbara, but not for long.

“I’d never heard of Ojai,” he says, “and just by luck I ended up in Ojai.”

Having decided to start an art commune, the Kochs signed up with a real estate agent who eventually steered them to an Upper Ojai ranch owned by the poet-actress-playwright Iris Tree, an Englishwoman who had founded the High Valley Theater and co-founded the Ojai Music Festival (which originally featured drama as well as music). By 1952, Tree was spending most of her time in Carpinteria and Santa Monica, so she rented her 23-acre Ojai ranch to the Kochs and Foster for $100 per month, along with Gerd’s promise to milk her cow and take care of her three horses. She also introduced him to the art critic Henry Seldis, who evidently was responsible for that Times piece — the first of many that would focus on Gerd over the next decade.

“When I first lived in Ojai I was always self-promoting,” he said in an oral history interview for the Focus on the Masters Archive and Library in Ventura.

This was despite being “super shy with lots of phobias,” he added. “But I made up my mind … I had to get hold of myself and work through those things.”

Gerd and his son Kear, about 16 years old, with a joint Ojai Art Center exhibition in 1972

The commune’s Upper Valley neighbors included two artists who worked in wood — Roy Patton, who carved marionettes, and Max Heinrich, a sculptor who lived across the road and helped Gerd round up Tree’s horses when they got out of their corral. Max was a real-life Red Baron type, a former German fighter pilot from World War I. He was also an uncle of the Lennon Sisters, singing stars on “The Lawrence Welk Show,” who occasionally visited his ranch.

Koch’s other Ojai friends included the ceramicists Beatrice Wood and Frank Noyes; the painters Gui Ignon and David Bridge; the California cuisine pioneers Alan and Helen Hooker, founders of the Ranch House restaurant; the gallery owner Kay McPherson, a granddaughter of the evangelist Aimee Semple McPherson; the siblings Kate and Arthur Hughes, Happy Valley School students and future artists; the architect Zelma Wilson; and miscellaneous eccentrics like the actor Norbert Schiller, who built a stone tower in his back yard. (It’s still there.)

“Ojai had so many interesting people,” Koch says.

He fit right in. What could be more interesting, in 1953, than a person who was starting an art commune? “Too early,” Koch notes. “It was ahead of its time.” Indeed, the commune broke up after only six months when Ray Foster pulled out. But Gerd and Irene doubled down on Ojai, buying the aforementioned two acres off of Shippee Lane for $1,000 per acre.

“The valley of Ojai is our experience,” Gerd and Irene jointly announced in 1956. “Not a sentimental experience but the strength of muted colors sun bleached, brilliant at twilight or during a rain … the beauty of homely things – of decayed wood, lichen, fungus, sage and buckwheat droppings. It is a feeling for the natural order of fallen limbs, leaves, and animal paths.”

When not painting or sculpting, Gerd worked as a janitor at the Ojai Playhouse movie theater, and as a gardener at the library. He also offered private lessons to budding artists like Frances Johnson, who would go on to a distinguished career as a Ventura County artist and museum curator.

“Frances was one of my first students when I came to Ojai,” Koch says. “I got her started.”

Later, in the ‘60s, Koch would begin teaching at the college level in Santa Barbara and Ventura. But in the ‘50s he focused more on his career as an artist. He was producing fine work, but L.A. tastemakers did not habitually look to Ojai to discover the next star artist. They did, however, beat a path to Ojai for the annual Music Festival – especially in 1955, when droves of them came to town to watch the celebrated composer Igor Stravinsky serve as a guest conductor. With Stravinsky due to return to Ojai for the 1956 festival, Koch had a brainstorm.

He noticed a vacant store on East Ojai Avenue, across from the Arcade. (The space currently is occupied by the Ojai Coffee Roasting Co.) The owner was in the process of remodeling it for his next tenant, and Koch took advantage of the transition to mount a pop-up “Gerd and Irene Koch” exhibit there for the duration of the Music Festival.

“I decided to have a show there but it was gutted,” he says, “so all my friends brought potted plants and we fixed it up real nice for three days.”

Cultivating L.A. connections soon led to Koch’s first big break in the metropolis.

In September 1956, Gerd and Irene were included in a seminal event for L.A.’s fledgling avant-garde art scene: A group show at Edward Kienholz’s brand-new and very cutting-edge NOW Gallery on La Cienega Boulevard’s Gallery Row. The exhibit was called “Action2: Works By West Coast Painters,” most of whom, like Gerd, were California abstract expressionists. When the group show finished its run, the Kochs took over the entire gallery for their own exhibit of paintings, drawings and sculpture.

“Gerd and Irene Koch live and cook on the ground on two acres in the Ojai Valley,” a Times reviewer wrote. “They translate the colors of growing things and earth about them into abstract painting of unusual beauty.”

Kienholz and Walter Hopps went on to found the famous Ferus Gallery, which featured Koch canvases along with those of Richard Diebenkorn and other future stars. The Kochs now had established a promising beachhead in L.A., but Gerd did not neglect the opportunity represented by the Music Festival. Another celebrated composer, Aaron Copland, was scheduled to conduct in 1958, and this time Gerd went all out.

He and Irene organized “The First Invitational Festival Exhibition of Southern California Painters,” with Seldis and Ojai art dealer James Vigeveno serving on the awards jury. The artists Gerd invited to participate were all certified big names (the prize winners included Peter Voulkos and Howard Warshaw). The exhibit was held at the Art Center, where Koch cleverly mounted a concurrent exhibit on the patio of the better-known Ojai Valley painters, with himself and Irene among the participants. Meanwhile, Koch friend Adele Bednarz mounted a special exhibit at her Gallery of Contemporary Arts, opposite the Oaks Hotel. As a final touch, Koch had Beatrice Wood and Esther Bruton Gilman hold open houses at their studios on McAndrew Road. Twenty-eight years before the advent of the Ojai Studio Artists tour, the Kochs and their associates created a valley-wide arts festival.

Like the Tree Ranch Road art commune, the Festival Exhibition turned out to be an idea ahead of its time. But Gerd was just hitting his stride. Later in 1958, he and Irene scored a two-person show at the Pasadena Art Museum (now the Norton Simon). They also started teaching art classes at the new (and soon to be legendary) Ash Grove nightclub on Melrose Avenue, a folk-music venue co-founded by their Ojai friend Kate Hughes and her boyfriend, Ed Pearl.

“I went down to L.A. quite often,” Gerd says. “Made a lot of connections. And we were winning a lot of awards.”

The big one for Gerd came in 1959 when his painting “Spring Garden With Sun Wet Path” won the top prize at a major regional exhibit hosted by the Los Angeles County Museum of Art.

“That really put me on the map,” he says.

Yet he and Irene remained in Ojai, far from the hard-partying Ferus Gallery scene. By this point, Hopps and his partners were beginning to move on from abstract expressionism to Pop Art and Conceptual Art, and from championing up-and-coming California artists to representing already established stars from New York.

“They became such giants that it went to their heads,” Koch says of Hopps and Kienholz. Moreover, he and Irene did not share the Ferus crowd’s enthusiasm for burning candles at both ends. The Kochs had a young son, Keari, to think about, and anyway they preferred the peace and quiet of Ojai. “We didn’t fit into the partying situation,” Gerd says. “That’s why we left.”

The Kochs switched to the more sedate Esther Robles Gallery and carried on. By now they were well known in L.A. as Ojai artists whose oil paintings and watercolors drew inspiration from their rural surroundings. “Nature Tints Their Palate,” a Times story proclaimed in 1961. “Gerd Koch Works Accent Artist’s Ojai Environment,” was a Times headline from 1963, over a story describing Gerd’s subject as “the lush, wild growth of grass and shrubs that surround his Ojai studio.”

But Gerd’s time in Ojai was approaching its end. After earning a master of fine arts degree from UCSB in 1967, he joined the Ventura College Art Department as a full-time professor. Preferring to avoid a daily commute, he moved to Ventura in 1969. Irene remained in Ojai, where she continues to reside today, and the couple eventually divorced. (Gerd and Carole Milton have been together since 1980.)

When Gerd retired from Ventura College in 1998 at the age of 69, he was lauded as a distinguished artist, an inspiring teacher, a generous mentor, a prolific curator, an indefatigable leader of international tour groups and a tireless promoter of the arts. At the time of his alleged retirement, he co-founded the Studio Channel Islands Art Center in Camarillo, and he has scarcely slowed down since.

“Gerd has always been a great organizer and promoter of causes dear to his heart,” says his friend Donna Granata, the founder and executive director of Focus On the Masters, and a former student of Koch’s. “Whether he is regaling a listener with his adventures of his numerous tours he organized to Europe, serving as a board member to a non-profit or championing the work of a fellow artist, Gerd shares his love and devotion to the arts every day … Gerd’s encouragement has set so many of his students on their career path, mine included. That’s why we call him the Godfather of the art community.”

Koch has continued to exhibit his work in galleries and museums. For one Studio Channel Islands exhibit, the Ventura County Star reported that he was keeping his prices reasonable so that art lovers of modest means could afford to buy a painting.

“All artists feel, particularly as they get older, that it’s better to distribute than to keep,” he told the Star. “One, so that more people can enjoy them. Two, I’m more comfortable when they’re out there instead of together in a bunch. I’m always afraid of fire.”

His fears were realized last December 4. Koch and Milton lived in her art-filled house on Via Cielito in Ventura’s Poinsettia neighborhood, near the top of a ridge. That night, a neighbor pounded on the door and warned them to get out now. Koch only had time to grab one of Milton’s paintings before the Thomas Fire roared over the ridge and reduced house and studio to ashes. Koch says he lost between 15 and 20 paintings and Milton lost even more. But they escaped with their lives and landed in Ojai, where the arts community has rallied around them. Their plan is to return to Ventura eventually, but in the meantime, Koch is back in his old stomping grounds, the place where he made his start, and where he learned a crucial lesson: To succeed as an artist, you have to take risks.

Thus Gerd on Tree Ranch Road at the tender age of 22, starting a ‘60s-style commune in the depths of the conservative 1950s. Thus Gerd planting his flag in the middle of nowhere on Calle Moreno and painting abstract expressionist landscapes for which no market had yet been established. Thus Gerd overcoming his shyness to become a relentless networker and promoter as he built a long and distinguished career as an artist and educator.

“Chaparral Morning Moods,” Gerd Koch

“I just do it,” he says. “I stick my neck out.”

Leave A Comment