Off the Shelf | By Kit Stolz

The Tortilla Curtain

So begins the final act of T. Coraghessan Boyle’s most controversial novel, The Tortilla .Curtain, which includes a wildfire followed by a mudslide — a potentially fatal disaster for all its central characters. It begins with a twist of fate. An Anglo nature writer driving through Topanga Canyon inadvertently clips and injures a young Mexican man, who with his teenage mate is trying to find work in Southern California. Unable to afford rent, the immigrant Mexican couple camp out in the canyon and, later in the fall, try to cook a gift Thanksgiving turkey over the fire. Inadvertently they set off a wildfire that all but destroys the development in which the Anglo couple lives.

Boyle, one of Southern California’s most prominent writers, and a distinguished professor at the University of Southern California, has published 14 novels and ten collections of short stories since the 1970s.

After the Thomas Fire, Kit Stolz of OQ’s “Off the Shelf” asked to interview him, because he is a writer who has often focused on environmental topics, including wildfires, mudslides, and climate change. He graciously consented to do so by email, even though his own neighborhood in Montecito was nearly destroyed in the debris flows of January during the course of the interview.

OJAI QUARTERLY: What drew you to the story of “The Tortilla Curtain?” And why do you think it has stood up to the passage of time since the book was published, over twenty years ago?

T.C. BOYLE: I grew up in suburban New York and moved to California in l978 to teach at USC. This translocation is, I think, what gives me a unique outsider’s look at the issues and environment of California. The debate about illegal immigration at the time I was writing “The Tortilla Curtain” in the 1990s wasn’t really a debate — it was yes or no, period. I took on the topic, presenting four points of view — those of an Anglo couple living in a gated community at the top of Topanga Canyon and of an immigrant Mexican couple living in the canyon itself, in order to broaden the debate.

Why has the book endured? Because of the hard sociological and environmental issues it takes on — and which remain unresolved. We are now seeing the effects of global warming, overpopulation, and the fight for resources globally. That’s not going to go away until our species is decimated by war, disease, and famine. We are all one and we are all equally subject to the laws of nature and we are in deep trouble.

STOLZ: How did you and yours fare in the Thomas Fire? And when you first heard of the fire in the Santa Paula area, could you imagine facing a threat to your home over a week later?

BOYLE: I’m fielding your question in the aftermath of yesterday’s debris flows that killed 15 of my neighbors, while 24 are still missing. (Final count as of press time — 21 dead) Let me say that the fire had me fully terrified and doubtful that our 109-year-old Frank Lloyd Wright house would survive. The rains? In relief — and oh, so short-sightedly — I welcomed them.

STOLZ: It’s apparent in Ojai and I expect in Montecito that we are not going to be “the same” anytime soon. Yet major disasters — fire, landslide, earthquake — made the dramatic landscape of Southern California. Santa Barbara, for example, is a city built on a landslide. Ojai has a history of monster fires. Is denial baked into our lifestyle? Are we dumb or freaking crazy — unable to see the amount of risk we live with?

BOYLE: See my story, “La Conchita,” about the disastrous mudslide in that community, which was first published in The New Yorker. Our memories are short. The sun shines. Nature smiles on us. Danger? What danger? When we evacuated in advance of the fire last month, I thought all Montecito would burn and knew how hard it would be to live anywhere else. I’ve lived in this house for 25 years now and I can’t imagine living anywhere else.

STOLZ: In the story, you describe a mudslide: I don’t know if the average person really has much of an idea what a mudslide involves…maybe it was the fault of the term itself — mudslide. It sounded innocuous, almost cozy, as if it might be one of the new attractions at Magic Mountain, or vaguely sexy, like mud-wrestling … but that was thinking of a limited sort. A mudslide, as I know now, is nothing short of an avalanche, but instead of snow you’ve got 400,000 tons of liquefied dirt bristling with rocks and tree trunks coming at you with the force of a tsunami. And it moves fast, faster than you would think.

It feels as if you’re trying to use your imagination to see beyond the obvious, and perhaps for that reason stories like “La Conchita” read almost like prescient visions of the future.

BOYLE: I must compliment you on choosing those apt quotes. Am I prescient? A little, I suppose — or maybe just ahead of the loop. As an environmentalist, I read widely about climate change, habitat loss, extinction — and the sustaining joys of nature itself.

STOLZ: Prominent climate researchers such as Sarah Myhre complain that the existential concerns of scientists about today can’t be heard in a national discourse dominated by a crass politician who has no apparent connection to the natural world. Do you ever feel that frustration?

BOYLE: I do feel that frustration, but in any case I must explore my concerns through fiction, as I am an artist, not a scientist. Art cannot be advocacy or it ceases to be art. But art can hit you in that hidden place where your emotions reside and that is the pathway to a deeper view of things.

STOLZ: Regarding climate change, you had a excellent and factual description in your novel “A Friend of the Earth,” from the perspective of an environmentalist struggling to live a sustainable life through floods and droughts in Santa Ynez Valley in the near future.

“Global warming. I remember the time when people debated not only the fact of it but the consequence. It didn’t sound so bad, on the face of it, to someone from Winnipeg, Grand Forks, or Sakhalin Island. The greenhouse effect, they called it. And what are greenhouses but pleasant, warm, nurturing places, where you can grow sago palms and hydroponic tomatoes during the deep-freeze of the winter? But that’s not how it is at all. No, it’s like leaving your car in the parking lot all day with the windows rolled up and then climbing in and discovering they’ve been sealed shut — and the doors too. The hotter it is, the more evaporation; the more evaporation, the hotter it gets, because the biggest greenhouse gas, by far and away, is water vapor. That’s how it is, and that’s why for the next six months (in Southern California) it’s going to get so hot (the local creek) will evaporate and rise back up into the sky like a ghost in a long trailing shroud and all this muck will be backed to the texture of concrete. Global warming. It’s a fact.”

BOYLE: When we look at global warming as a present fact, we get beyond the rhetoric of the environmentalists and the obstruction of the oil-company shills occupying the White House. Fiction is for dramatizing the problem, which also humanizes it.

STOLZ: There’s a fearlessness in your writing — a willingness to dive into seemingly almost any plight or any character’s perspective, be it past, present, or future. Is that willingness to dig deep and take dramatic risks your message, as it were, to readers? To turn us on to possibilities? To not settle for the expected, but to dare to think big?

BOYLE: I like the way you put it, Kit. But I am not consciously transmitting any message beyond demonstrating the joy I take in making art and presenting it to you. I do like to push boundaries in my fiction, though, rather than playing it safe. For me, anything can be the basis of a story — and I can set a story anywhere and see it through any character’s eyes. Or at least that’s what I attempt to do.

STOLZ: You have a great gift for satire, for making fun of people, all sorts of people, from the horny teenagers of “Greasy Lake,” to “eco-nuts” and idealists of all sorts, to cynics like big game hunter Mike Bender, and on and on. Yet you also have a knack for making even misguided characters deeply sympathetic despite their foolish mistakes. How do you know when

you’ve found a juicy character, worthy of following and exploring over the course of a novel?

BOYLE: I don’t. I just follow the story. Of course, in the case of historical figures like Frank Lloyd Wright, Alfred C. Kinsey, Stanley McCormick, John Harvey Kellogg (and in my just-completed novel, “Outside Looking In,” Timothy Leary) I found myself drawn to such characters. But sometimes characters sneak up on me, like Sarah Hovarty Jennings, the anti-authoritarian zealot of “The Harder They Come.”

STOLZ: People in Ojai who suffered losses in the Thomas Fire have shared their sense of “overwhelm” — an inability to think clearly, or plan wisely, or even take in a full-scale disaster. You live in Montecito, and though you and your family survived, no doubt you were affected by what happened. People often look to storytellers for emotional wisdom. How did you deal with the disaster on a personal level, and do you have any possibly helpful advice to offer?

BOYLE: Ground zero of the disaster here, at the junction of Hot Springs and Olive Mill, is two blocks from my house. We are among the lucky ones. We suffered no physical damage, but the psychological toll is incalculable. (My essay on the fire/flood disaster here, “The Absence in Montecito,” was posted by The New Yorker Online on on Jan. 21.) As for advice, I have none, other than to come together with your neighbors in mutual sympathy.

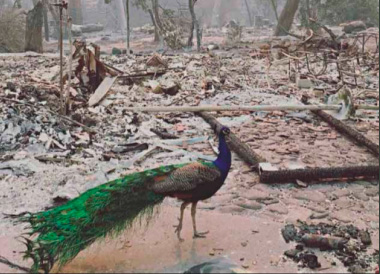

STOLZ: A neighbor took this picture (page 48) in her neighborhood in Upper Ojai a few days after shortly after the Thomas Fire hit Upper Ojai. To me this seems very much like a T.C. Boyle moment: a spectacular animal in a crazy situation that evolution may never have expected, surviving by its wits and its sheer determination to live. (Like the boar and the rattlesnakes in “When the Killing’s Done,” for example.) Does this kind of survival in the post-apocalyptic future inspire you? Make you smile? Make you wonder? Are there human lessons to be drawn here?

STOLZ: A neighbor took this picture (page 48) in her neighborhood in Upper Ojai a few days after shortly after the Thomas Fire hit Upper Ojai. To me this seems very much like a T.C. Boyle moment: a spectacular animal in a crazy situation that evolution may never have expected, surviving by its wits and its sheer determination to live. (Like the boar and the rattlesnakes in “When the Killing’s Done,” for example.) Does this kind of survival in the post-apocalyptic future inspire you? Make you smile? Make you wonder? Are there human lessons to be drawn here?

BOYLE: Among the sad pictures of the destruction here in Montecito is one of a bear on our beach (below) the morning after the rains. It appears on my Twitter feed and was posted by one of the followers on my site. The animals are taking their chances out there too — and

they have no choice but to adapt to our ways. Which is why, as Richard Leakey pointed out some years back in “The Sixth Extinction” (one of the seminal texts I absorbed when I wrote “A Friend of the Earth” in 2000, which projects to 2026 and concerns global warming and the alarming disappearance of species worldwide) we are living in a world of rapidly dwindling diversity. Black bears are commensal with us and doing just fine, thankfully. But if you want to weep, weep for the polar bears. We are just now seeing the very last of them fade away into extinction. Of course, we’re on the way out too — we just don’t realize it yet.

Leave A Comment