Bridles & Brahmins

An Ojai Rebel’s Journey from Ranch Trails to the Temples of India

Over the last 40 years, Stephen Huyler has published a half-dozen books on the sacred arts of India, drawing on his countless excursions and tours there, often to little-known rural regions far off the tourist track. He has become a living bridge of sorts between English-speaking nations and the arts and crafts of its many peoples, including its indigenous tribes.

Over the last 40 years, Stephen Huyler has published a half-dozen books on the sacred arts of India, drawing on his countless excursions and tours there, often to little-known rural regions far off the tourist track. He has become a living bridge of sorts between English-speaking nations and the arts and crafts of its many peoples, including its indigenous tribes.

Huyler has organized exhibits of Indian arts and crafts for the American Museum of Natural History and the Santa Barbara Museum of Art, among other museums, and exhibited his photographs of the peoples and art of the vast nation at the Smithsonian and the Asian Art Museum in San Francisco. But he insists he writes primarily for the interested public, both in India and at home, and not just for academics and experts.

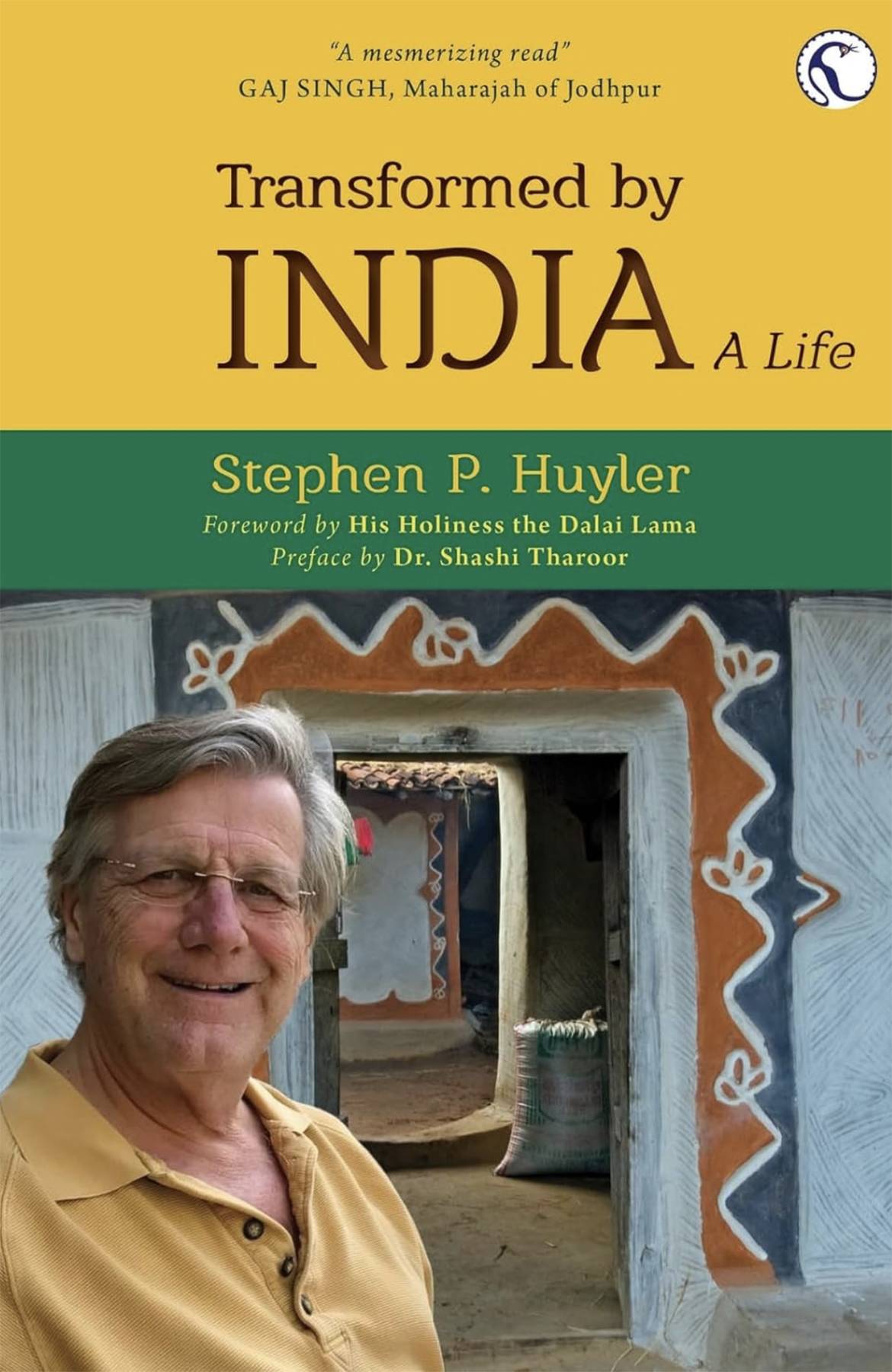

Now for the first time he has told his own story (with a warm foreword from the Dalai Lama, no less). The release of the book — “Transformed by India: A Life” — has set off a veritable flood of admiring reviews from scholars and the reading public in India (where it was first published). Later the book was released in the U.K., and in August in the U.S.

On the way to becoming an honored guide and scholar of Indian arts and craft, Huyler turned his back on his father’s cowboy ways at Thacher, which dominated his upbringing.

Huyler maintains a connection to Thacher and Ojai today, but on his own terms, and only after a full-scale youthful rebellion against his upbringing. As the youngest of three children fathered by Jack Huyler, who taught at Thacher and led its legendary horse-riding program for many decades, Huyler spent his summers in Jackson Hole, Wyoming with the family. He was raised by his father to be a cowboy.

“We were raised on horseback,” Huyler recalls. “I could ride before I could walk. My father was a product of the cowboy mentality that you can see in a show like “1883.” I think it’s a very good series, because it shows what those people were struggling with, and why they became as hard as they did.”

Huyler goes on to talk about what happened to Kim, the horse that he “grew up on and with.”

“Kim was in his mid-20s, and wouldn’t have made it through another winter at Jackson Hole,” he said. “A huge hole was dug by backhoe. I had to go into the field and put a halter on him, this horse I loved like family, and lead him up to the pit. My older brother had to shoot him in the skull and then we both had to push him into the pit. It was a horrific thing to do, but that was the cowboy mentality. You take care of your own. You don’t ask someone to do it for you. You face life as it presents itself to you. You learn self-reliance.”

Huyler — speaking on the phone from Camden, Maine, where he has lived for more 40 years — chuckles a little ruefully.

“Those messages, they’re still in me somewhere,” he says.

“Though I’ve fought against it with every fiber of my being.”

BREAKING AWAY FROM THE COWBOY LIFE

Today, in his 70s, Huyler speaks frankly and without hesitation of being bullied as a boy, and how fundamentally the brutal treatment he endured as a shy child changed the course of his life. At the age of six or seven, he said, an older boy twisted his arm behind his back until the pain was all but unbearable. In that moment Huyler vowed silently to himself that he would never treat anyone that cruelly, a vow he says he has honored all his life.

Today, in his 70s, Huyler speaks frankly and without hesitation of being bullied as a boy, and how fundamentally the brutal treatment he endured as a shy child changed the course of his life. At the age of six or seven, he said, an older boy twisted his arm behind his back until the pain was all but unbearable. In that moment Huyler vowed silently to himself that he would never treat anyone that cruelly, a vow he says he has honored all his life.

When he reached high school, even though he could have attended the elite boarding school Thacher, instead he went away to a different school on Catalina Island for his first two years.

“At Thacher, my father would have been my instructor, and that wouldn’t have worked for either of us, because we were enemies,” Huyler said. “By the time I joined Thacher for my junior and senior years, I had already learned how to distance myself from Dad.”

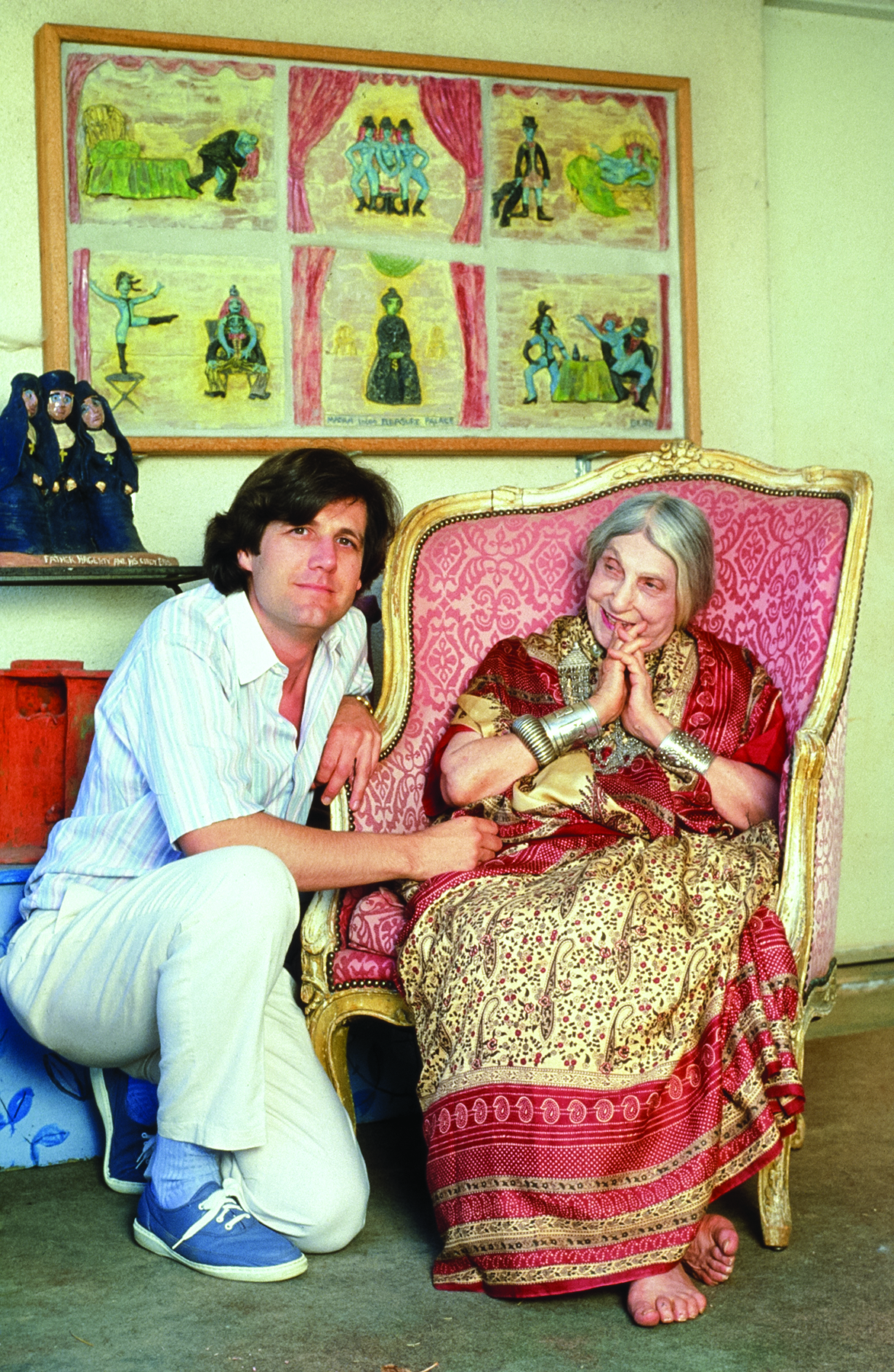

Huyler’s life changed course when he came home from a not-especially-successful first year at college. He needed work for the summer, and asked his neighbor, Beatrice Wood, the artist and ceramicist, if he could help her out in her studio. Though Wood was world famous and sophisticated, and loved for her saucy wit, she readily agreed to the teenager’s request.

“I categorically refused to be typecast by my father, or put into a mold,” Huyler said. “His image of what he wanted for a son was antithetical to everything I wanted. It was really Beatrice, who also had rebelled against her upbringing, who truly understood who I was. She saw I wasn’t wrong in what I was looking for, and what I was trying to do.”

ENTER BEATRICE WOOD

“This is my gigolo, Steve Huyler,” Wood would say on outings with teenage Huyler, to shock old ladies in town, but she took Huyler’s future — as a would-be scholar in the arts — seriously. At the University of Denver, Huyler had planned to study Native American arts and crafts, to honor their indigenous traditions, but the faddish popularity of all things Native American in the early 1970s pushed Huyler — always averse to following the crowd — to rethink.

“This is my gigolo, Steve Huyler,” Wood would say on outings with teenage Huyler, to shock old ladies in town, but she took Huyler’s future — as a would-be scholar in the arts — seriously. At the University of Denver, Huyler had planned to study Native American arts and crafts, to honor their indigenous traditions, but the faddish popularity of all things Native American in the early 1970s pushed Huyler — always averse to following the crowd — to rethink.

“I brought that to Beatrice and she said, ‘When I was in India, I found the craftsmanship and folk art fascinating, and yet there was almost no one documenting it. You could carve out a career for yourself.’ She was very, very clear.”

Wood, too, had rebelled in her youth. She had broken away from her stuffy upper-class upbringing, and became famous as a muse for defiant Dada artists such as Marcel Duchamp. But ultimately she was betrayed by her husband, an inveterate seducer, and never found much happiness with a male partner. (As discussed in a previous “Off the Shelf” story in the Summer 2022 issue of Ojai Quarterly about the book, “Spellbound by Marcel.”

Wood’s life changed profoundly when in 1962 she was invited by one of Gandhi’s most trusted advisors — a woman named Kamaladevi Chattopadhyay, a leading figure in India’s arts and crafts movement — to bring her work to India. This began a lifelong association between Wood and India, which became part and parcel of her identity as a woman and artist.

“I think that the way the remarkable generosity of India has healed me, the person I am today, that remarkable generosity had the same effect on Beatrice,” he said. “I think what it gave her was a sense of security, a sense of being valued for who she is.”

OVERLAND TO INDIA IN 1971, WITH BACKPACK

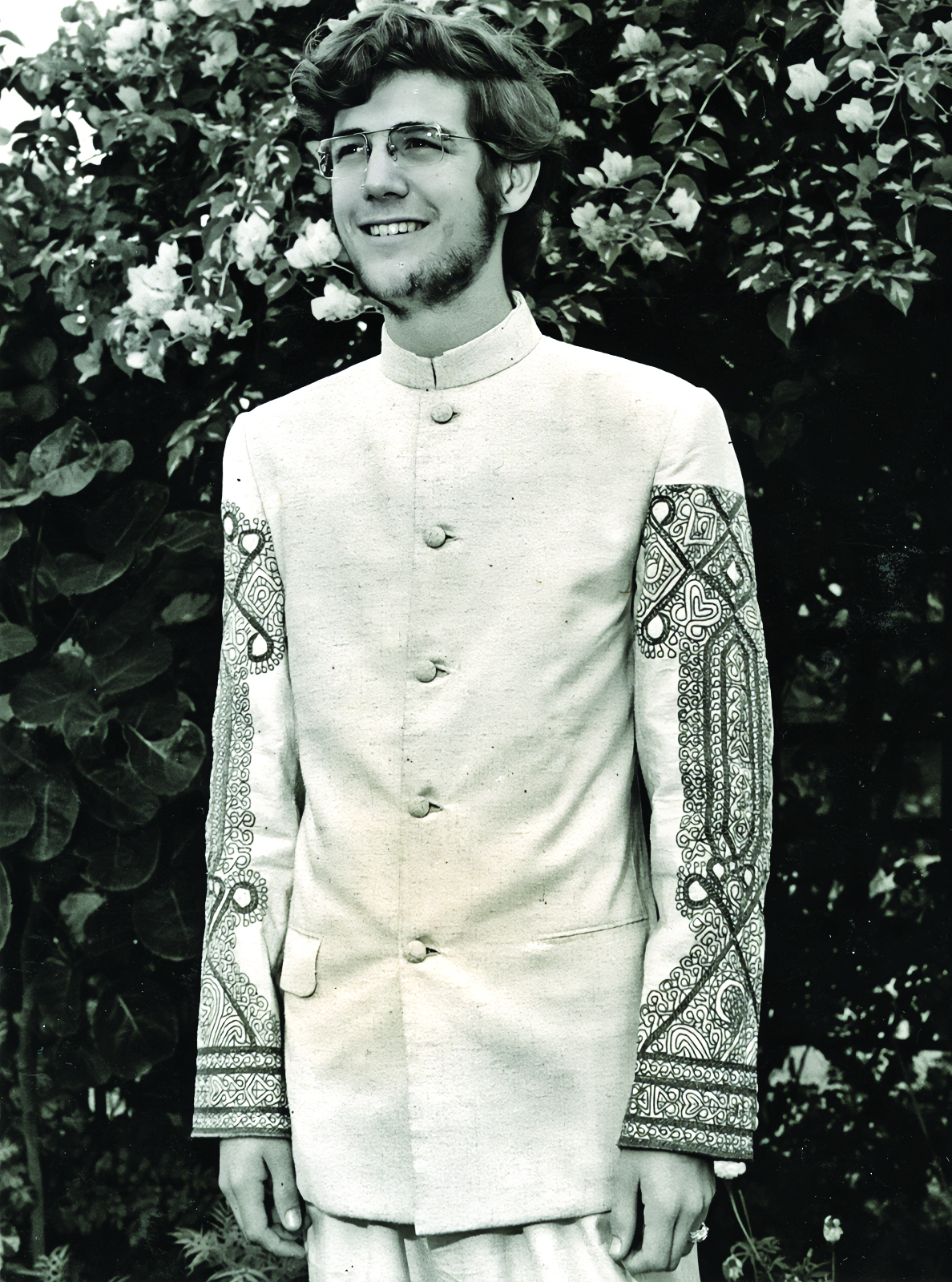

In early 1971, Beatrice Wood invited Huyler to join her on a trip to India. The invitation changed everything for Huyler. As a first-year student at the University of Denver, he had been enthusiastic but “too distracted” to focus on his studies.

Within a month he became an A+ student, eagerly learning about India’s arts, history, and culture. When Wood wrote later to say that she had to cancel the trip, he decided to go on his own, and persuaded the university to allow him to major in the study of India for several different departments, the only student allowed that independent course of study.

His method was to follow an individual object of art into the past, tracing its values — social and often religious — in meticulous detail. His professors were impressed with his drive, he wrote, and he was granted a year of credit in his junior year for field research in India, a rare honor for an undergraduate.

Huyler spent months preparing for an overland journey to India from Turkey, through Iran, Afghanistan, and Pakistan. Old issues — as old as 1896 — of National Geographic proved to be his best guide to the many cultures he would encounter on his nine-month trip. He said goodbye for the time to the girl he met and fell in love with at age 16 in Ojai — Helene Wheeler, whom he went on to marry — and flew to Paris, and then set out on the weary and clattery Orient Express railroad for his journey to Istanbul, his first stop.

In September, Huyler reached the eastern Turkish border, where he boarded a barely functioning bus patched together after a nearly fatal accident. On this, he and a handful of frightened passengers from around the world would journey on narrow roads through mountainous Turkey to Iran, a difficult journey marred by a humiliating bout of amoebic dysentery.

In contrast to the people of Iran, who were largely hostile to Americans, the 19-year-old Huyler was greatly impressed with the lively and curious people of Afghanistan he found eight years before the invasion by the Soviet Union, and decades before the American-led Global War Against Terror. He passed through Pakistan quickly, as at the time Pakistan was on the verge of a war with India, and Huyler knew he had to cross into India before the already militarized border was closed. And so he entered India alone, at a remote crossing, on what happened to be his 20th birthday.

MEETING INDIA

After crossing the border, with few options available for transportation at his remote spot, Huyler pedaled a bicycle rickshaw the first few miles into India. Leaving the border and its war behind, he traveled by train to Amritsar, where the Golden Temple welcomes pilgrims and visitors of all sorts into the dazzling heart of the Sikh religion.

After crossing the border, with few options available for transportation at his remote spot, Huyler pedaled a bicycle rickshaw the first few miles into India. Leaving the border and its war behind, he traveled by train to Amritsar, where the Golden Temple welcomes pilgrims and visitors of all sorts into the dazzling heart of the Sikh religion.

Fascinated by the spectacular murals on the temple walls, Huyler searched out an expert. A dignified old gentleman, G.S. Sohan Singh — the son of the last artist to paint the murals — welcomed him into his studio, despite Huyler’s lack of an introduction, and showed him dozens of paintings his father had made while creating the murals. Huyler didn’t have enough money to buy such exquisite works at that time, but Singh agreed to set aside a few, until Huyler could return to pay him, even if that took years.

“From entering the temple, sitting in quiet meditation, falling in love with its art, searching out and meeting an accomplished artist, and creating a bond … I was setting a tone for the next half-century,” Huyler wrote. “And this was only my second day in India!”

Huyler caught another great break when, thanks to an introduction from Wood, he met her close friend Kamaladevi Chattopadhyay, whom he describes as “a tiny old woman in a plain grey cotton sari, (who) grimly invited me to sit in her flower-filled garden while she poured us cups of tea.” Huyler did his best to charm her, to no avail: she was unsmiling and brusque, although she asked questions about the six-month route he intended to take throughout India, to learn about its arts and crafts, and how he hoped to make it a lifelong pursuit. She made wise suggestions, and said in her “dry and humorless voice” that she would write letters to artists, weavers, artisans, and craft organizations throughout India, requesting that they host Huyler in their homes.

“On that day, Kamaladevi launched my entire career!” Huyler wrote in astonishment. Later, he learned that she had been one of Gandhi’s closest advisors, spent decades as a leader in the non-violent freedom movement, and endured five years in prison for her resistance to British rule in the 1930s. Years later she launched India’s first weaving centers and arts cooperative. In the decades that followed, he developed a close friendship with her.

This was only the beginning of Huyler’s first tour of India, visiting famous sites such as the Taj Mahal and Varanasi, by the Ganges River, and reuniting with Beatrice Wood, who was on a lecture tour speaking of American arts and crafts for USAID.

Meanwhile his faithful girlfriend, Helene, had managed to convince her parents to allow her to join Huyler in India for two weeks, if chaperoned. Shortly after she arrived, Huyler proposed, and Helene accepted. Deciding that they were married in spirit, and would soon be married in fact, they spent a blissful two-week honeymoon traveling in South India. (Fifty years later, Huyler says it’s still a happy union.)

THE SACRED & TRIBAL ARTS OF INDIA

Huyler has returned to India many times, often with Helene. He has canvassed the country conducting a cross-cultural study of rural arts and crafts, particularly focused on women’s art. It was on his first trip with Beatrice Wood, exploring ancient temples in the southern Tamil Nadu region, and staying as an honored guest at the homes of artists and leaders in the arts and crafts movement, that he found his life-long inspiration.

Rukmini Devi, another good friend of Wood’s, the charming and articulate founder of India’s largest school of classical music and dance, helped him explore little-known traditional arts, including women’s ephemeral paintings. And in South Indian villages, he and Wood discovered large and small terracotta horses placed under the trees, as votive offerings to the gods, an art he finds fascinating.

“Beatrice and I were exhilarated: the figures we found were charming, diverse in form and style, and expressive of the personal whimsy of each sculptor,” he writes.

This underappreciated art became the focus of Huyler’s doctoral thesis, and he still feels a deep connection to both the art and the artists who work in that tradition, and the spiritual tradition from which they come. In 1979, despite harassment from local officials who considered the indigenous Adivasis peoples backward and not worthy of Western attention, he found the Dongria people, who live according to ancient traditions in small villages in the wild, and worship a local mountain. Although a — possibly corrupt — local official soon evicted him from the region by military escort, Huyler maintains a connection to the art of the Adivasis.

He points out that these peoples comprise the largest tribal population in the world, over 100 million people whose languages predate Sanskrit and who often face prejudice in India.

For Huyler, they are comparable to the Native Americans, with whom he feels empathy, in part because he had been both bullied and tormented as a young person.

“I believe that I am sensitive to downtrodden people because of the bullying and abuse I endured as a child,” he said. “My decades of work with the women of India has been in part an attempt to give them voice and recognition, to let them tell their unheard stories, and how they find their own creative solutions to their inequities.”

A MUCH-HONORED BOOK TO BE FEATURED ON OJAI’S PODCAST, “TALK OF THE TOWN”

“Transformed by India: A Life” was published first in India earlier this year, to an outpouring of acclaim from both scholars and ordinary readers in Amazon reviews. In June it was released to the U.K., and in August, North America.

Huyler has in the meanwhile recorded a version for Audible, which is also available now. In September, Ojai Podcast “Talk of the Town” will feature an extensive interview with Huyler, who is currently conducting a U.S. lecture tour he intends to bring home to Ojai on November 1, 2025, at the Ojai Arts Center, and to the Santa Barbara Museum of Art the next day. He promises a visual treat, unveiling the heart of traditional Indian arts and crafts.

Leave A Comment