FEATURE | By Mark Lewis

Lightning in a Bottle

How Michael Owens’ bottle-making invention – ‘the most complicated machine ever built’ – funded Edward Libbey’s reinvention of Ojai

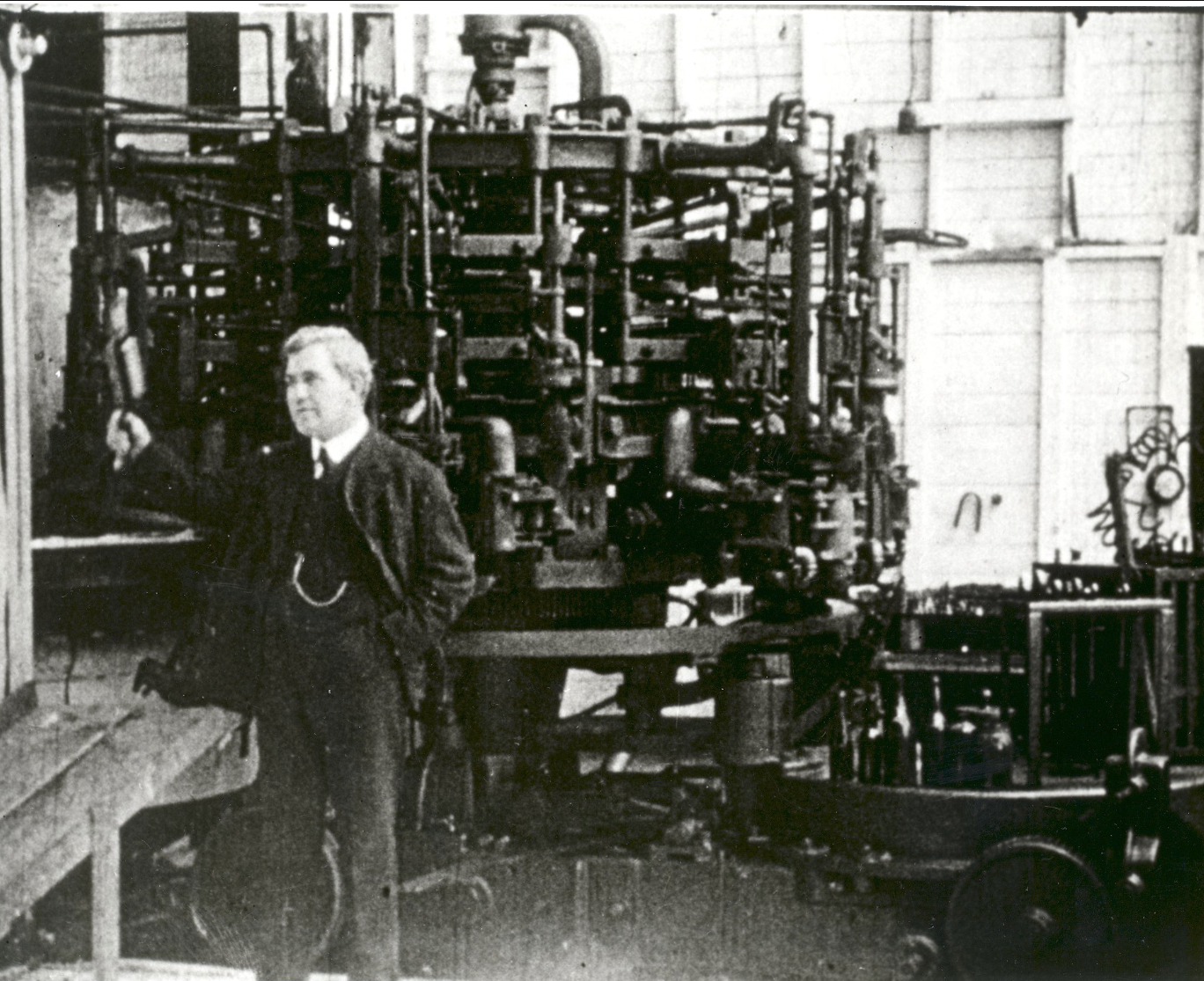

Owens with bottle-making gadget

HISTORY CREDITS the Ohio glass magnate Edward Drummond Libbey with transforming the dusty town of Nordhoff into the beautiful, Spanish-style village he renamed Ojai. And Libbey deserves that credit. But he had considerable help from a man who was mostly a stranger to this town – Michael Joseph Owens of Toledo, Ohio.

Owens was the Libbey Glass Co. employee who invented the fiendishly complicated Automatic Glass Bottle Making Machine that enabled Libbey to dominate the glass industry.

“Without Owens’ invention, Libbey would not have been nearly as rich, and probably could not have afforded to spend the $1 million or so that he lavished on his Ojai project,” said Ojai historian Craig Walker. “That’s at least $17 million in today’s dollars.”

Unlike Libbey, whose Boston Brahmin family had come over on the Mayflower, Mike Owens was the uneducated son of an Irish-immigrant coal miner. His bottle-making machine revolutionized the glass industry and made him a millionaire. It also made Libbey a multimillionaire, who could easily afford to transform Nordhoff into Ojai with a wave of his checkbook. Most people in Ojai today know Libbey’s name, but very few have heard of Owens. This is his story.

‘

MICHAEL OWENS was born in Mason County in rural Virginia on New Year’s Day of 1859. At the age of 9, he followed his father into the coal mines. But soon he suffered an injury at work that prompted his mother to switch him to a glass factory in Wheeling, W. Va., where she thought he was less likely to come to harm.

In the factory, 10-year-old Owens “worked 60-hour weeks,” the historian W. Kesler Jackson wrote in an article about the inventor. “He was paid 30 cents a day. He went home each night covered in ash and coal dust. It’s a fair bet that his lungs were full of ash and dust too.”

In those days, glass products were created by hand by highly skilled glassblowers, each one assisted by a team that included young boys like Owens. Each team produced about a bottle per minute. Owens worked hard and learned every aspect of the production process. In his 20s he became an activist in the glassblowers’ union, which zealously resisted any move toward automation. But then the ambitious Owens decided to become a manager.

Young boys were used extensively as glass-blowers

Stubborn and hot-tempered, Owens had an irascible personality that put off many potential employers. But Edward Libbey saw something in him — and Owens saw something in Libbey, even though at the time, the Libbey Glass Co. was struggling financially. In 1888, Owens moved from Wheeling to Toledo to join Libbey’s management team.

“Owens would bring problems, but he would also revolutionize how glass was made, and would save Libbey Glass,” Quentin R. Skrabec Jr. wrote in his Libbey biography. “The Libbey-Owens team would be one of the greatest business partnerships of all time.”

Owens was very successful at managing Libbey’s Ohio factories, including one that produced glass light bulbs to go with Thomas Edison’s revolutionary new product, electric light. Owens also built and managed the enormously successful Libbey Glass Pavilion at Chicago’s legendary 1893 World’s Fair.

But Owens soon became obsessed with an even bigger project. He wanted to invent a machine that would completely automate the bottle-making process. For some 2,000 years, glass bottles had been hand-crafted one at a time by highly skilled artisans. Owens envisioned a mass-production machine that would be operated by unskilled workers at a small fraction of the cost. Libbey decided to back him.

This was a very risky move. By way of comparison, at about the same time, Mark Twain famously went broke investing about $300,000 in an extremely complicated typesetting machine which kept breaking down. Libbey had better luck with Owens’ even more complex bottle maker, introduced to the world in 1903. Contemporaries sometimes called it “the most complicated machine ever built.”

With its 10,000 parts, including ten rotating legs with claw-like appendages, the 30-ton machine looked like a nightmarish steampunk monster out of a novel by H.G. Wells. But it worked.

“It took Owens five years to produce it, then a few more to perfect it, but in the end (and after burning through half a million of Libbey’s investment dollars) he’d done it,” historian Kessler wrote. “Within just a few years, Owens’ automated bottle-making machines could crank out almost 250 bottles per minute!”

Owens’ machine rendered the master-craftsmen glassblowers obsolete and eliminated the demand for young boys to work in glass factories, as Owens himself had done. (Ironically, Owens was no crusader in the fight to abolish child labor. “Young or old,” he once said, “work doesn’t hurt anybody.”)

Automation and mass production of glass jars and bottles produced a revolution in how food and drink were made available to the masses. Owens’ machine represented the biggest innovation in glass-making in 2,000 years. It changed the world.

Of more relevance to Ojai, the machine made Libbey extremely rich. Further contributing to Libbey’s fortune over the years were other Owens technical innovations in the manufacture of plate glass, which allowed for larger windows; and laminated safety glass for automobile windshields, a brand-new market in the early 1900s.

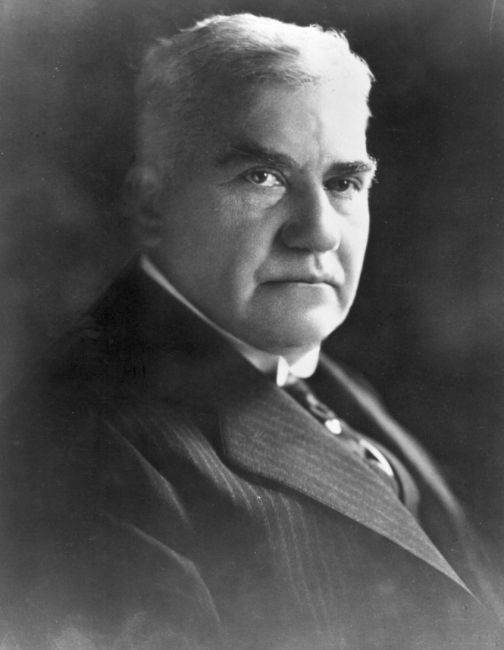

Edward Drummond Libbey

As a result, Libbey was able to divert some of his focus from his glass business to his interest in art and the City Beautiful movement. First, he created the Toledo Museum of Art. Then he discovered Ojai and had his epiphany about giving its downtown district an ambitious Mission Revival makeover. Thanks to Mike Owens and his machine, Libbey didn’t have to think twice about whether he could afford it. He simply went ahead, and the results are all around us today: The Arcade, the Post Office Tower, Libbey Park, the Hotel El Roblar, the Ojai Valley Library, the Ojai Valley Inn and the Ojai Valley Museum (which began life as St. Thomas Aquinas Catholic Church).

This past October, Ojai officials bolted a new bronze plaque to the west end of the Arcade, noting that the state has placed downtown Ojai on the California Register of Historical Resources. The plaque credited this move in part to Ojai’s “association with Edward Drummond Libbey.” The text mentions Libbey several times but makes no reference to Owens. But during the winter of 1922-23, he did finally visit Ojai and admired Libbey’s project, which Owens himself had done so much to make possible.

Thanks to his bottle-making machine, the self-educated Owens eventually ceased to be Libbey’s employee and became his business partner instead. When Owens died at 64 in December 1923, The Ojai newspaper ran a front-page obituary, and Libbey eulogized him as “one of the greatest inventors this country has ever known.

“It’s not like he’s forgotten,” Craig Walker said. “He’s in the National Inventors Hall of Fame, and his legacy is reflected in the names of two of today’s Fortune 500 companies, Owens Corning and Owens-Illinois. But he should be better remembered here in Ojai, given that his inventions helped pay for all these historic buildings we celebrate.”

Leave A Comment