FEATURES | By Mark Lewis

The Battle for Ojai’s Soul

Ojai Rancher K.P. Grant died a century ago, but the fate of his property is an ongoing saga with the finale yet to be written

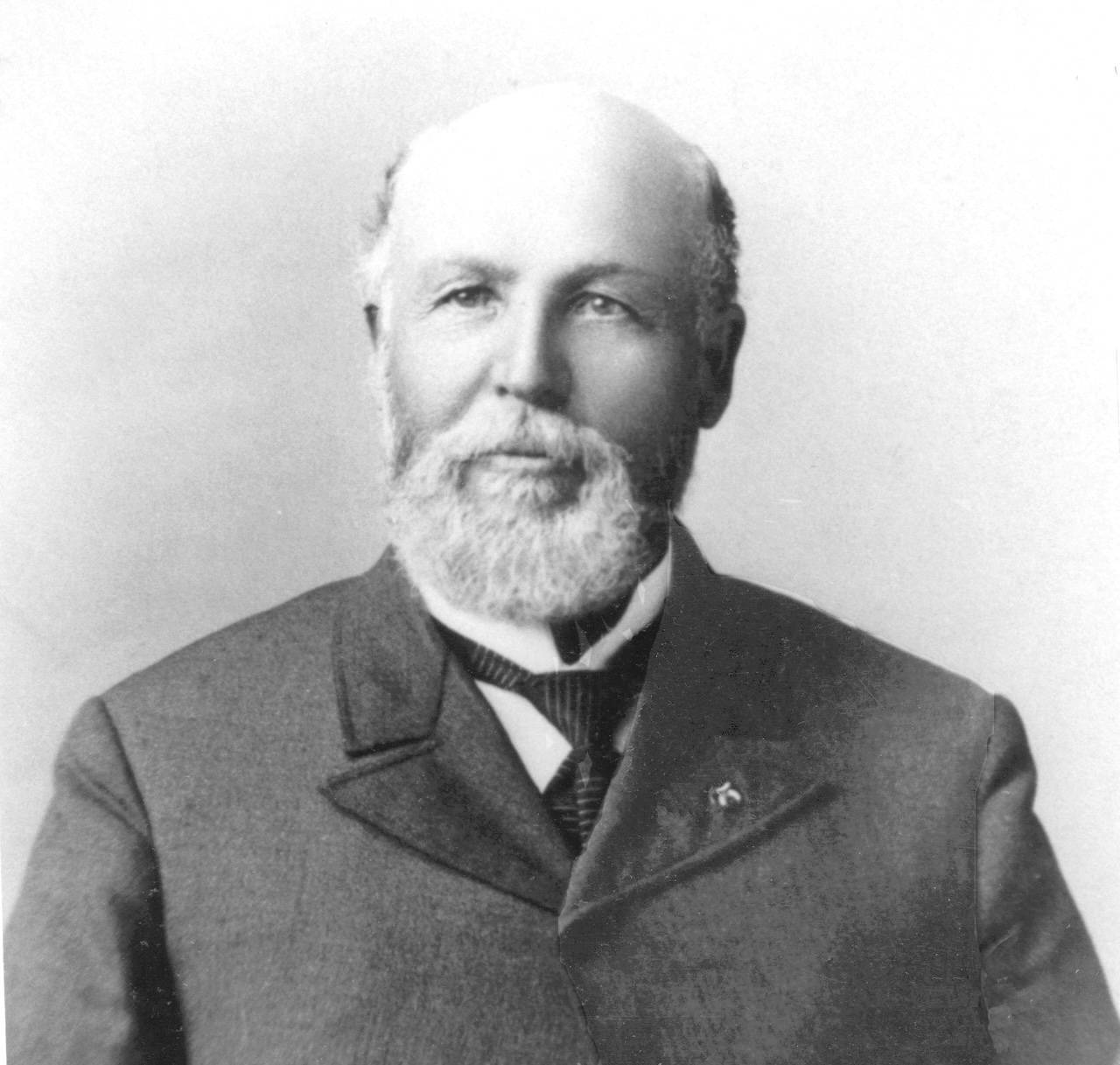

Kenneth Grant

LAST YEAR for the Fall issue, the Ojai Quarterly ran a piece we called “West Side Story,” about the epochal events of 1924, when three big West Side ranches separately were developed into Villanova Prep, the Krotona Institute of Theosophy and the brand-new town of Meiners Oaks. This issue, we present a sequel of sorts to “West Side Story.” It concerns a fourth big West Side ranch that changed hands in 1924 – the K.P. Grant Ranch.

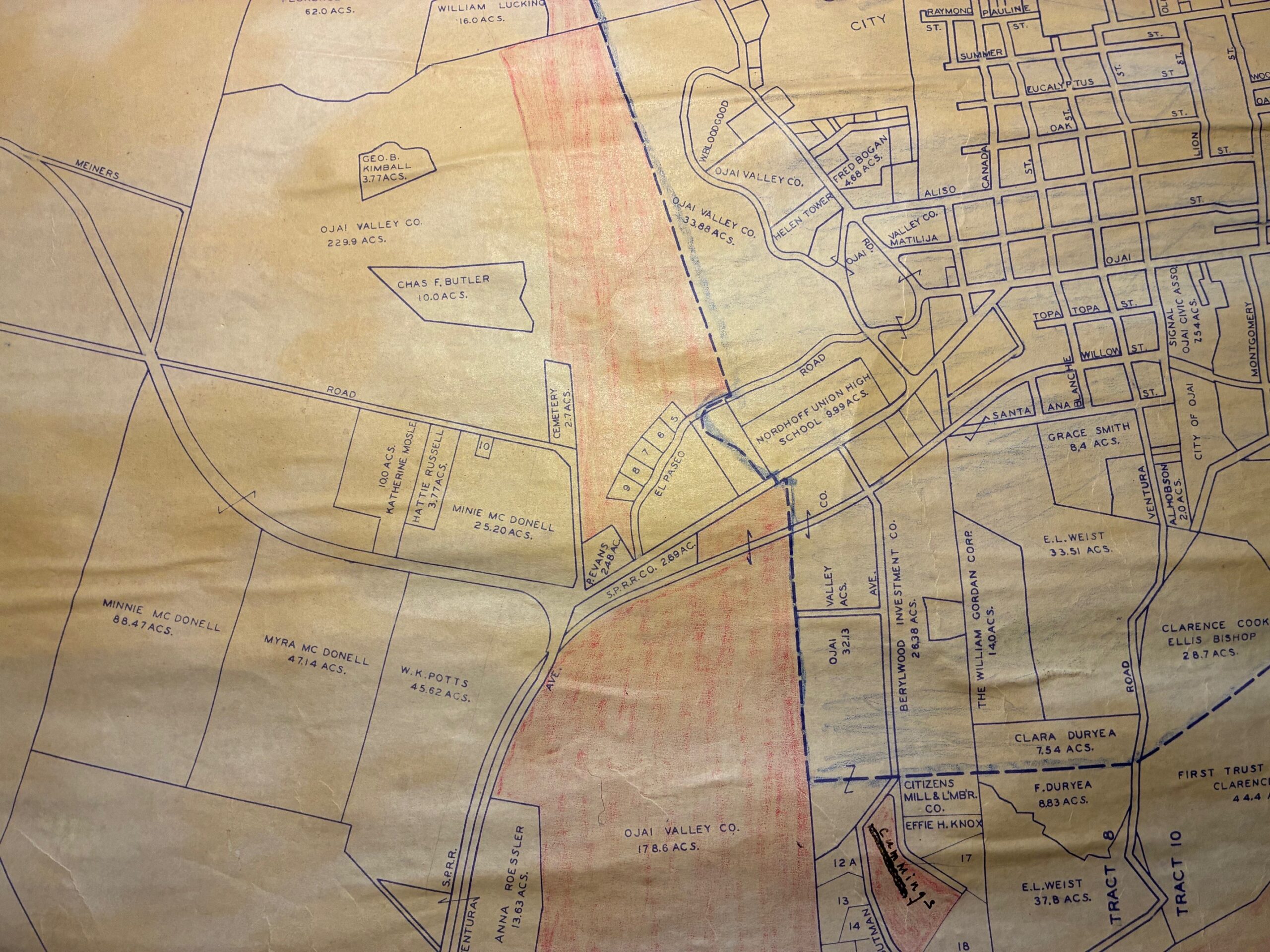

The Grant Ranch did not, at first, end up in the hands of developers, which is why we left it out of “West Side Story.” But over time, chunks of it were sold off and turned into the Y shopping center, the Caltrans yard, the hospital and nearby medical offices, the Ojai Terrace and Taormina neighborhoods, the Hitching Post and Creekside condo developments, Nordhoff Junior and Senior High School, a big part of the Ojai Meadows Preserve, and the stretch of Highway 33 that runs from the Y to the Deer Lodge.

After all these years, just one chunk of the old Grant ranch remains unsold. You likely know it well: The 14 vacant acres of weeds and wildflowers that sit across the 33 from the high school and the Meadows Preserve. The address is 1450 Maricopa Hwy. A developer from Beverly Hills agreed to buy it two years ago with a view to putting up a huge apartment building complex there. But the deal fell through before escrow closed.

Why does that one chunk of the ranch remain unsold, after all these years? It all goes back to 1924, when K.P. Grant died. His ranch passed to a large group of heirs, one of whom married a developer named Edwin Carty. In the 1950s and ‘60s, Carty sought to consolidate as many Grant Ranch parcels as he could and turn that stretch of Maricopa Highway into a retail and residential district. His own mother-in-law sued him for fraud, but she lost.

Carty encountered more effective resistance from local folks such as City Councilman James Loebl, who feared that Carty’s plans “would ruin Ojai as we know it.” An epic political battle ensued, followed by an epic legal battle, as everybody fought over the legacy of K.P. Grant. The saga reminds local historian Craig Walker of HBO’s recent hit series about a patriarch and his three children, who fought one another for control of his media empire.

“The story of the Grant Ranch is Ojai’s own version of ‘Succession,’” Walker says.

BORN IN CANADA in 1842, Kenneth P. Grant arrived in Ventura around 1870 and set out to make good. He flourished as a blacksmith, an undertaker and a carriage maker, and later gave the city the acreage that now comprises Grant Park. He moved to the Ojai Valley in 1891 and established the 342-acre Grant Ranch, where he raised plums for prunes, grain, apricots and other crops. His ranch was bounded on the east by Del Norte Road and what is now the Ojai Valley Inn; on the north by Cuyama Road (then called Meiners Road); on the south by what is now Krotona; and on the west by the big Meiners ranch, now Meiners Oaks.

“His ranch house — Grantwood — was located on the southwest corner of Del Norte and Cuyama, across from the cemetery,” Walker says.

Grant served a term as county supervisor for the Ojai district. He also served on the committee that brought the railroad to the valley in 1898, and he donated the land that became the line’s Matilija Station. (It’s now the site of Rotary Park.) He helped E.P. Foster acquire Camp Comfort in 1904 and arrange for it to become the county’s first public park. He was, in short, a man who gave generously to the community. And not just his time and money, but his land. Finding that his ranch was bigger than it needed to be, he began selling off pieces of it at $100 per acre, even though he said it was worth $200 per acre.

“It is a shame,” he said, “for men to hold more land than they can make use of, while honest, deserving poor men are compelled to do without, simply because they haven’t money enough to buy large tracts.”

Grant and his second wife, Tonie, both died in 1924. They had no children, so K.P. left his ranch to his late sister’s descendants. Initially, the main beneficiary was his niece Minnie McDonell, who lived at the ranch and kept it going, and mostly intact, until her death in 1948. At that point, control of the ranch passed to numerous heirs, including Minnie’s niece, Doris McDonell Carty of Oxnard. Doris was married to Edwin Carty, a county supervisor and developer.

“After Minnie’s death, the family began selling off parcels under the direction of Carty, an ambitious, politically savvy family scion whose vision for the property was often at odds with the community, the Ojai City Council, and even his own family,” Walker says.

Ed Carty

ED CARTY was born in Santa Barbara in 1897. He met Doris while they were attending Ventura High School and married her in 1919. The couple settled in Oxnard, where Ed ran the Carty family ranch. Eventually he turned his hand to politics, serving as mayor of Oxnard during the ‘40s and as the Oxnard district’s county supervisor from 1952 to 1965. He also became an extremely successful developer, starting with his family ranch, which he subdivided for residences. When Doris inherited part of her own family’s ranch in Ojai, Ed had some ideas about what they should do with it.

Grant Ranch 1935

“Carty’s vision was shopping centers, housing tracts, commercial development, condos and apartments,” Walker says. “He persuaded the family members to join the properties together, claiming they would be worth more. He promised all the family members their shares would be respected. That didn’t happen, and Myra McDonell, Doris’s mother, sued Carty and her own daughter for fraud. There was no written agreement, so Myra lost the case.”

According to contemporary news coverage in the Ventura County Star, Myra had inherited 25 acres of the Grant Ranch from her late husband, Charles McDonell, with the proviso that she in turn leave the acreage to their son Bruce, Doris’s brother, “as a stake to help him in life.” Somehow those 25 acres ended up in Ed Carty’s hands, and he declined to return them. Myra filed suit against Doris and Ed in1955, but it was dismissed the following year, and Bruce was out of luck.

In the years that followed, another Grant Ranch heir sold a parcel to developers who planned a big shopping center at the Y, to be anchored by a Safeway supermarket. (It’s now a Vons.) The Ojai City Council refused to approve the project. They had seen how the downtown districts of Ventura and Oxnard had withered when new shopping centers were built on the outskirts of town.

“And this did begin happening here,” Walker says. “Stores, businesses, and public services that catered to locals began moving to the Y or Mira Monte, and stores downtown started going out of business.”

The Council didn’t want that to happen in Ojai. But the developers managed to put the issue to a vote of the people, and in 1959, Ojai voters overruled the Council and approved the Y shopping center project.

When that shopping center opened in 1960, Carty proposed to build another one further up the Maricopa Highway on unincorporated county land. As a powerful county supervisor, he made sure his land there was zoned for high-density commercial use. Ojai officials feared that Carty’s plan would lead to uncontrolled development all along the highway outside the city limits. To gain some control over the situation, the city approached Carty with a request to annex his land. Carty was willing — so long as the parcel he wanted to develop retained its zoning.

“They wanted to incorporate it,” Carty said in an oral history. “They begged us to come into Ojai.”

City officials informally agreed to leave his zoning unchanged, and the land became part of Ojai in 1964.

At the time, Caltrans was in the process of widening Highway 33 from two lanes to four. That’s why Maricopa Highway from the Y to Cuyama Road was, until recently, the only four-lane road in Ojai. It was supposed to eventually connect with the four-lane freeway that was advancing from Ventura toward Ojai in stages. But that freeway got no further north than Foster Park, because in the late ‘60s, a coalition of local activists rose up against it. They feared the development that always follows in a new freeway’s wake.

Many of these same anti-freeway activists decided to stop Carty’s retail project while they were at it. (Among them were Pat Weinberger, John Taft, Winnie Hirsch, and Craig Walker’s father, the architect Rodney Walker.) A new City Council majority was elected in 1970, and they promptly changed the zoning on Carty’s land. No high-density commercial development allowed.

Jack Fay, a holdover from the previous Council, was outraged that the city had gone back on its word.

“The city invited him in, on the understanding that the zoning would remain the same,” Fay told an interviewer some years ago. “We had a moral obligation to him, and he got stuck.”

Borrowing the strategy of the Y shopping center developers, Carty launched a successful petition to put the matter to a vote of the people. Feelings ran high during the campaign, and few people in town were indifferent to the outcome. But Ojai’s attitude toward development had done a 180 since the previous vote in 1959. When the special election was held in January 1972, an astonishing 70.4 percent of eligible voters turned out, and they voted 3-to-1 against Carty. James Loebl hailed the result “a mandate of the people for the kind of ruralness and atmosphere we want here in Ojai.”

Carty, who felt he had been unfairly vilified during the campaign, called the election result “a payday for slander.” A powerful mover-and-shaker whose circle of influential friends included former California Governor Earl Warren, Carty was not accustomed to taking “no” for an answer. He sued the city to restore his original zoning, and he won at the district court level. But the city appealed and ultimately won the case. When Carty died in 1990, his Maricopa Highway parcel remained mostly vacant. And it’s still vacant today.

Carty Lot

SOME FIFTY YEARS LATER, Ojai’s downtown is vibrant and charming, but most of its shops and restaurants now cater more to visitors than to residents.

“Fortunately, downtown Ojai was saved by some modest redevelopment projects that revitalized the area while preserving the town’s historic character,” Walker says. “It was also saved by the area’s many historic buildings that attracted tourists. As the locals moved out, the tourists moved in, helping to save the small-town character of Ojai as it was in the 1920s.”

Locals still do much of their shopping at the Y, but no big new shopping center has been built on Maricopa Highway since 1960. The highway’s four lanes are now two, thanks to the recently completed Phase I of the Active Transportation Project, which gives more room to bicycle and pedestrian traffic. The new bike lane runs along the southern flank of that last unsold piece of K.P. Grant’s old ranch. Carty’s heirs still own it, and currently they’re asking $14 million for it, or $1 million per acre.

There are six Carty heirs who share ownership of the property, according to Edward Carty, who with his sister Anne runs an antiques business in Montecito. Five heirs, like Edward and Anne, are grandchildren of Edwin and Doris Carty; one is a great-grandchild.

Two or three years back, local Ojai environmentalists led an effort to raise enough money to buy the land. They fell short, and the property was sold — provisionally — to the aforementioned Beverly Hills developer, Henry Shahery. He informed city officials of his plan to put up nine large apartment buildings, each one 10 stories tall, comprising a total of 2,500 one-bedroom apartments. About 500 would be reserved for lower-income people.

Edward Carty says the heirs did not know about the developer’s extremely high-density plan when they agreed to sell him the land.

“We had no idea!” he says.

You’re thinking, what? No way that sort of monstrosity would ever be built in Ojai. And you’re probably right. Nine 10-story towers crammed onto 14 acres? This may have just been an

gambit from a developer who possibly envisioned settling for something less ambitious. But even a project only half as big might have spelled the end of Ojai’s pretensions to being a semi-rural community with small-town charm.

Ojai’s zoning laws, conforming to its general plan, forbid high-density residential development in that area. Shahery & Co. sought to exploit a technicality that could let him invoke the so-called Builder’s Remedy, which allows developers to supersede local zoning laws if a city’s housing element is not in compliance with state law. City officials pushed back against his strategy, and they must have been persuasive, because last fall Shahery canceled the property purchase before escrow had closed.

But, with the California Legislature passing all sorts of laws to combat NIMBYism and add much-needed housing across the state, it’s no surprise that this developer was tempted to take a shot at developing the Carty parcel. Shahery and his associates ultimately folded their tents and went away, but the property is still for sale, and Sacramento is still leaning heavily on towns like Ojai to allow more housing to be built — especially “affordable” housing. What’s to stop other developers from trying their luck there? And who’s to say one of them might not succeed?

“At some point, somebody can just cram something down their throat,” Edward Carty says.

“I’d hate to see something modern and inappropriate there,” he adds. “It should be as beautiful as the Arcade downtown, or the Ojai Valley Inn.”

Capitalism, like nature, abhors a vacuum. Those 14 acres will not remain vacant forever. Perhaps, as Craig Walker suggests, it would behoove the community to proactively foster a development there that would use the land in ways that benefit Ojai, without destroying its small-town ambience in the process. That would at long last write a happy ending for the K.P. Ranch saga. After all, the Y area today provides vital services to the community, and its development did not doom the downtown district. It might even have saved it.

“In the 1960s, the Y area development, of which Ed Carty was the public face, was seen as an evil force by most locals,” Walker says. “But perhaps in the end, it was a necessary evil, because by drawing development toward the city’s West Side, it shielded Ojai’s beautiful and historic downtown buildings from the ravages of modernization. It is a question for the community to ponder as we move forward into an uncertain future.”

Leave A Comment