By Mark Frost

Ask around and you’ll find almost everybody in town has a story about Bill. A friendly encounter in line at the post office. A sideline chat between parents at a soccer or rec league basketball game. A surprise appearance, raising people’s spirits at a post-mortem election dinner. All united by a common takeaway: Pleasant surprise that he seemed so friendly, so real, so down-to-earth, so interested in you. So “not-Hollywood.”

Ojai’s attracted more than its share of show business “royalty” over the years, all the way back to the silent era, when child mega-star Jackie Coogan cruised through town in his chauffeured Rolls, or Charlie Chaplin and Great Garbo showed up for lunch with Krishnamurti. A steady stream of “fame refugees” have sought sanctuary here ever since, a retreat from the pressures of the grinding, cutthroat business lurking behind Hollywood’s phony glamorous façade. The valley’s reputation as a healing center, a place to lick your wounds, or seek your true “self” is more than genuine. The ideal spot for that “second home” to strike a balance with the bruising rough-and-tumble of Tinseltown. That quest has delivered a succession of stars to the doorsteps of our finest realtors and frequently straight into escrow. More often than not these seekers end up bouncing right back out again, within a year or two or five. Not the “right fit.” Too — what’s the right word — “rustic.” More often than you’d imagine the lack of “restaurant diversity” is mentioned. And so the restless celebrities continue their search for sanctuary elsewhere.

Sometimes, truth be told, and by whatever quasi-mystical means one might use to describe such a deliberation, it seems the valley decides you’re not right for it. (And — per Seinfeld — not that there’s anything wrong with that.) The folks who stick around come to feel that, for a wide variety of reasons, they belong here. Those who don’t move on. And the valley, through some sub-sonic frequency, quietly affirms the call.

Bill and Louise Paxton, young newlyweds, found Ojai in 1991. They bought a rambling, ramshackle ranch house out in the — then — not quite as fashionable East End. Most recently owned by a successful screenwriter, before that it had been home to a die-hard commune of alternate-lifestyle hippies, and before that, when it was built in the ‘40s, a citrus rancher’s modest bungalow. Far from a household name at that point, Bill was just beginning to make his mark in memorable supporting roles, most notably for his friend director Jim Cameron in “Aliens.” The couple fell in love with the Ojai Valley, the solitude, peace and quiet, languorous rhythms and seductive beauty. The valley welcomed them. Surrounded by citrus and avocado groves, they put down roots.

Bill and Louise Paxton, young newlyweds, found Ojai in 1991. They bought a rambling, ramshackle ranch house out in the — then — not quite as fashionable East End. Most recently owned by a successful screenwriter, before that it had been home to a die-hard commune of alternate-lifestyle hippies, and before that, when it was built in the ‘40s, a citrus rancher’s modest bungalow. Far from a household name at that point, Bill was just beginning to make his mark in memorable supporting roles, most notably for his friend director Jim Cameron in “Aliens.” The couple fell in love with the Ojai Valley, the solitude, peace and quiet, languorous rhythms and seductive beauty. The valley welcomed them. Surrounded by citrus and avocado groves, they put down roots.

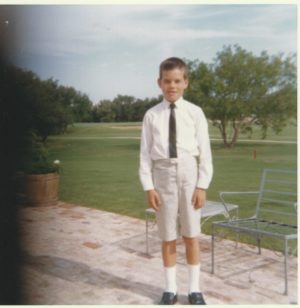

Bill hailed from Fort Worth, Texas, the son of John Paxton, a prosperous businessman from Kansas City who’d inherited and successfully carried on his father’s firm, selling hardwood to furniture manufacturers throughout the mid-South. After John married Mary Lou Gray, a former model and fashion director for a Chicago department store chain, they moved to Fort Worth — a more central location for John’s expanding business — and raised their four kids. Bill always credited his parents with providing a worldly education, steeped in high and popular culture, with a deep appreciation of literature, as well as the fine and performing arts. John was not only becoming a serious collector of some of America’s best artists, he secretly harbored a childhood passion he would only get a chance to indulge years after his retirement: he wanted to be in the movies. Over time that dream slowly seeped its way into young Bill’s ideas for his own future as well.

Bill hailed from Fort Worth, Texas, the son of John Paxton, a prosperous businessman from Kansas City who’d inherited and successfully carried on his father’s firm, selling hardwood to furniture manufacturers throughout the mid-South. After John married Mary Lou Gray, a former model and fashion director for a Chicago department store chain, they moved to Fort Worth — a more central location for John’s expanding business — and raised their four kids. Bill always credited his parents with providing a worldly education, steeped in high and popular culture, with a deep appreciation of literature, as well as the fine and performing arts. John was not only becoming a serious collector of some of America’s best artists, he secretly harbored a childhood passion he would only get a chance to indulge years after his retirement: he wanted to be in the movies. Over time that dream slowly seeped its way into young Bill’s ideas for his own future as well.

Letters of introduction from John to some of the screen’s golden age luminaries like Howard Hawks and Hal Wallis — friendships his dad had fostered on the course at Shady Oaks Country Club in Fort Worth, Ben Hogan’s home turf — brought Bill west to Hollywood after high school at the age of 18. He knocked around for a while without much luck, then gave New York University’s theater department a year, before landing back in Los Angeles for good. He fell in with a group of like-minded actors, writers and musicians, made a splash with some music videos he directed — one, “Fish Heads,” was broadcast on Saturday Night Live — and by happenstance found his first real break working in the art department of a forgettable Roger Corman sci-fi quickie. He quickly impressed the Canadian-born production designer on that picture with his boundless energy and cheerful can-do attitude, and an enduring friendship was born. That commanding, no-nonsense fellow was James Cameron.

>A few years later, while in London shooting one of his first supporting parts in a studio picture, “The Lords of Discipline,” Bill spotted a lovely young English woman waiting for a bus. Their eyes met for a moment, and in a flash Bill jumped on board after her and turned on the charm without even knowing where the bus was headed. “Twickenham, it turned out,” he’d say with a grin. “Wherever that was. But faint heart never won fair lady.” Five years later they were married.

As Bill’s career advanced — work that would eventually take him around the world, building a body of work whose range and popularity rivals that of any actor of his generation — the Paxtons restored that East End ranch house to suit their down-home needs and tastes, and fashioned the perfect place to raise a family. Their son James joined them there in 1994; daughter Lydia followed three years later. Over the years, as more opportunities arrived, Bill’s career strategy evolved from “say yes to everything” to the luxury of picking and choosing. He often turned to fellow actor and Ojai neighbor Malcolm McDowell – one of Bill’s acting idols — for career advice.

“At that point in his life Bill was a wild stallion, running on adrenaline and moxie,” Malcolm recalled recently. “But he’d started to realize he needed a bit of craft to go with it, and to his credit he worked hard to get it.”

When more studio jobs followed, Bill found he could afford to become more selective about the leading roles starting to come his way in independent pictures. A sea change in the movie business had begun: As the majors morphed into purely corporate enterprises they turned more and more to global audiences for their core business. A swing-for-the-fences mentality gradually took over the executive suites but bigger budgets meant studios needed to downsize their risk; a steady stream of “B” pictures with “A+” budgets became the strategic center of their portfolio. But an impulse within the creative community to keep on creating “cinema” for an audience still interested in grown-up, provocative pictures persisted. In these years before the rise of premium cable on television – which would ultimately replace them – the late ‘80s and ‘90s became a kind of mini-golden age for the American art house movie.

As one of the few actors who kept a foot in both the mainstream and independent world, this enabled the more artistically ambitious side of Bill’s instincts to find his way. He developed an eye for sharp material, not just for the part on offer, but for the story: Interesting, complex characters who were there to serve a good narrative or theme, not the other way around, and many of his choices were memorable: a punk urban vampire in “Near Dark,” the haunted sheriff in “One False Move,” leader of a down-home family of grifters in “Traveler,” the morally troubled older brother in “A Simple Plan.” All films willing to consider and explore the darker side of the American dream. A clear aesthetic had emerged through these choices, and this dual track strategy led him inevitably toward a desire to produce and eventually direct. His directorial debut in 2001 — “Frailty,” a disturbing Southern Gothic horror story about toxic distortions of religion and masculinity — confirmed the conclusion: Bill was a filmmaker.

• • •

A big part of what grounded Bill — and what made him so accessible and likeable on screen — came from the distance he continued to maintain between his personal and professional selves. Keeping his home and family life in Ojai throughout his career, away from the PR nonsense and castle intrigues of movie business politics, helped his equilibrium. As a group, movie stars run an occupational risk of commoditizing themselves into reliable “products” that studios lean on to sell tickets. Nowhere near as much fun as it’s conventionally perceived, it’s a far from enviable existence that can isolate and separate these quasi-mythical demi-gods from the prosaic joys of everyday existence. “Fame” — that elixir our culture reveres as a means to escape or defy whatever troubles vex us — is in many ways deranging.

That Bill had worked his way up on the other side of the camera — performing virtually every job on a picture — helped inoculate him against its perils. Even when he’d climbed to the pinnacle, the rarified position in the business known as Number One on the call sheet — AKA “leading man” — he insisted on seeing himself as just another member of the crew. Every project develops its own particular culture over time and Bill loved the nomadic camaraderie of life on the set, but he’d learned that its tone and chemistry depended on the attitude of the people at the top of the sheet; producers, directors, leads. He made a point, in the early days of any picture, to learn every last person’s name. Making the set a better workplace doesn’t guarantee a better outcome, but it helps create a better human environment in which good work can thrive. The creation and maintenance of that culture mattered to him, an attitude far from universal in the business. The notion of hundreds of artists united in the pursuit of a common artistic vision may sound hopelessly idealistic in such a bottom-line business, but if your goal is to entertain or inspire your fellow human beings, why settle for anything less?

My time with Bill began 15 years ago. He’d made a movie with my sister 10 years earlier, we knew each other’s work and had a lot of friends in common, but we’d never met. The occasion: he wanted to direct a picture I’d written, based on a book of mine, and I came away thinking: So that’s what happened to Huck Finn when he grew up. From the start I knew he was either going to sell me something I didn’t even know I wanted to buy, or we were going to go paint a fence together. The first time you meet him and he gives you his full attention it was a little like being caught in high beams. He was a top-shelf salesman, a skill integral to his principal occupation; this was also, I learned later, a legacy from his father. He seemed so high energy, alive to the moment, and available; but this wasn’t just about selling. I later realized he was like that every other time you were with him, too.

So we ended up painting that fence, when he directed “The Greatest Game Ever Played.” We had a supportive studio and a budget that was more than adequate to the task but wasn’t going to cause them any sleepless nights, and we were on a somewhat distant location in Montreal, doubling for early 20th century Boston. But Disney’s lack of heavy-handed oversight or creative interference owed more to the crystal clear impression of clarity and control they received from Bill’s leadership. He was brilliant with casting and actors and crew. His instincts for picking the right department heads were unerring and he enabled them to do their finest work. He had cast iron stamina — honestly, the sheer weight of the job half-kills you; you give over your entire life to it — but throughout he appeared to have the energy of five men. He was tenacious and he could be fierce in defense of his ideas but was invariably open to the possibility of a better one, no matter where it came from, and he was always able to hold his over-all conception and design in every particular. I’ve never worked with a director who was more committed to getting every single detail exactly right.

The white-hot maelstrom of film production is always a potent revealer of character, but a casual trip to an art museum with Bill one Sunday proved revelatory: I learned his life had, from the start, always been dedicated to art. He was a serious collector of serious painters, another gift from his father — who was a very serious collector and had raised Bill to become a patron of the arts. According to his good friend, renowned artist and Ojai neighbor Mick Reinman, the result was clear: Bill had a discerning, expert eye.

“It showed in his own collection,” says Mick. “He didn’t buy off the rack. It was all eclectic, personal, particular to him. He learned the habit of studying and buying art from his dad, but he ran with it further. It was in his blood. And he was a really talented artist himself. Every time he took a cell phone picture it looked like art. The book of writings and drawings he did about his trips down to the Titanic for that documentary with Jim Cameron is exquisite stuff.”

A good working definition of an artist is someone who goes through life refining their ability to perceive truth and beauty in the world and in people, and communicating that in the work they produce. Although he was invariably modest about his own abilities — he always insisted on calling himself a craftsman — by this criteria Bill was an artist in the fullest sense of the word. Directing a movie brings together every discipline of the arts into one comprehensive effort — it’s as demanding a profession as you could hope to find, to the degree that only a rare handful ever master it. If you had to reduce it to a single quality it might be this: film directing is, quite simply, the possession — and ability to effectively convey to others — of good taste. Another close friend and colleague, David  Blocker, produced both of Bill’s films.

Blocker, produced both of Bill’s films.

“To most people, Bill’s filmmaking talents were overshadowed by his acting achievements, but Bill was an incredibly talented director,” says David. “He had great passion for film and his knowledge of all the arts was vast. People might not have known that about him because of the easy way he carried himself, but he had a deep comprehension and understanding that always surprised the experts working in his filmmaking orbit. He was a monumental talent in front of and behind the camera.”

Bill’s favorite metaphor for film directing was an orchestra conductor; you clearly don’t know how to play every instrument as expertly as each individual artist, but you had damn well better know enough about it to persuade them to play the music the way you believe it ought to be heard. That’s the heart of the job of the person in that rickety canvasback chair with their name on it. Although he developed a number of other projects, including one that was close to going into production, “Greatest Game” turned out to be the last movie Bill ever directed. This is another genuine loss, as he already shared a characteristic common with every exceptional filmmaker: he applied to every aspect of the process a ferocious commitment to rooting out the truth of what the scene was trying to say, what the character was trying to say, what the line was trying to say, and how his next shot was going to service all of the above.

• • •

So, a year and a half of your life goes by, utterly consumed. You go out on the road to sell the finished picture — as you might suspect, this part came easily, second nature to Bill. Then you wait. In our case, the opening weekend was disappointing. The studio had already confessed they weren’t entirely sure how to market a period golf picture to a “modern, four-quadrant audience.” You steel yourself to the possibility of disappointment, but when you get that call on the first Saturday morning and the numbers aren’t what everyone had hoped for it breaks off a little piece of your heart.

And that’s, as they say, show business. The experience recedes into the distance. Often, usually, that’s the end of it. Relationships fade. You might catch the picture on cable some day down the road. Maybe you’ll watch, maybe you’ll switch it off. The memories, given the outcome, might be too painful. But a funny thing happened to “Greatest Game” once it made its way into the DVD and home video market. It landed. Found the audience that had been there for it all along. Within two years it had turned a profit. The Golf Channel made it a centerpiece of their play list. Fans of the game, fans of the genre, people who knew nothing about the sport at all, started calling it a classic. The same description that Bill had always been convinced it could one day achieve.

A few years later we attended a special screening together in Boston — the occasion was the 100th anniversary of the real event the book and film had celebrated, the victory of Francis Ouimet, the first American-born US Open Champion in 1913. Later in life, Francis started an educational charity to help poor kids who’d worked as caddies get a college education. Today the Francis Ouimet Scholarship Fund gives away over a million dollars a year to deserving recipients in Massachusetts. Five thousand people packed the Boston convention center that night, and as a bonus we spent a full day with the Fund’s other honoree, the King himself, Arnold Palmer. Six years after the fact, Bill got to take the victory lap he deserved.

We took a walk down Boylston Street that night. It was a few weeks after the Boston Marathon bombing. The street was lined with flags and posters for “Boston Strong,” and near the explosion sites, piles of shoes. Sobered, we hardly said a word. In an uncertain world, the resilience and character of the city that had produced Francis Ouimet was on full display. “Ain’t that America,” Bill said.

The year before my family and I had moved from LA to Ojai. Bill’s relentless salesmanship about the valley had, over time, proved irresistible. Lucky us. We found the place we’ve called home every since, and the welcome Bill and Louise provided to “Shangri-La” – seen through their eyes — made that feel like it had always been here waiting for us.

• • •

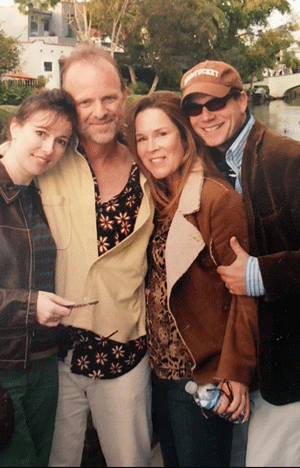

Bill had a lot of gifts, but arguably his greatest was his gift for friendship. Most of those close pals he’d knocked around with during his salad days in LA — the fellow dreamers you so easily lose touch with once success waves its wand at you — were still part of his life. The longer you knew him the more you came to realize he possessed an astonishingly wide range of acquaintanceship. If you were ever out in public with him, and saw the kind, self-effacing and graceful way he interacted with people who approached him, you’d instantly know why. He was interested in everything and everybody in a way that said we’re no different, we’re all brothers and sisters. We may be standing in different places, but we’re all on the same ground.

Bill Paxton was utterly unique and at the same time he seemed like… everybody. He had some kind of primal American DNA stamped on his soul. That helps explain his range; over four decades he played nearly everybody. One of the reasons folks loved Bill so much on screen is that just about everybody could see a piece of themselves in him. I think there was another reason as well: He was a genuinely good person and, in the mysterious alchemy that occurs between lens and subject, the camera read that like an MRI.

I’ve also come to think that, in any age, Bill would have had a memorable career on our silver screens. The studio system would’ve known exactly how to utilize his prototypical American nature and his particular set of skills, perhaps even more efficiently than in these last 40 years. Who knows? His presence was so vivid, so vital and full of life that people at any time and place would have responded to him in the same way.

The downside now — for those of us who knew him personally — is that his absence is equally oversized. His sudden, tragic loss still shocks and bewilders, feels senseless and strange. On a local level, he’d woven his life into our community, drawn strength and derived character from it, and given both in return. It might be nothing more than the filter of my own idiosyncratic response, because of his key role in bringing us here, but for me Bill and our town remain woven together, in some fundamental way, inseparable. We’d seen a good amount of each other over the last few years. He was used to a high-octane pace and had a somewhat restless soul but it’s comforting to know that he appeared to have recently reached a pleased and peaceful place in his life, taking stock, appreciative, feeling blessed. He and Louise seemed closer than ever. James and Lydia had both left the nest, successfully taking their first steps into adulthood. Whatever demons Bill wrestled with over time — and every artist does — it seemed that he’d gained the upper hand. That was good to hear and know and, now, remember. The valley is laden with memories of good times spent with him here for me, as it is for all his friends. Over time, the sense of loss they carry with them will surely undergo some sort of alchemical transformation into gratitude, bank into the kind of warmer flame that sustains you through colder days.

That’s my hope, anyway.

Leave A Comment