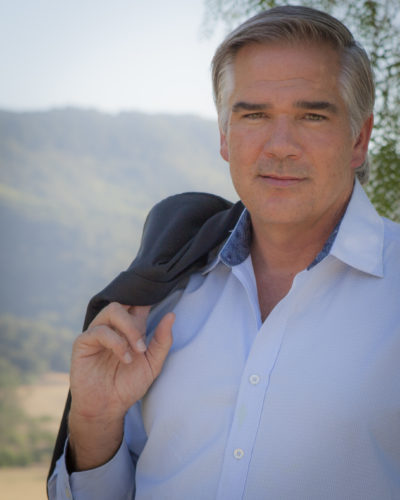

EDITOR’S NOTE | By Bret Bradigan

The People Who Teach Us, and Police Us

Bret Bradigan, editor & publisher of Ojai Quarterly and Ojai Monthly

Ojai style is characterized by a sense of sprezzatura — of graceful ease, of long leisurely talks on weighty matters, by style and sensibility, of contemplation amid the astonishing natural beauty that surrounds us. However, behind the scenes, there’s a lot going on — it’s hard work to make Ojai life seem so easy.

It’s our teachers, our police and humble service workers who make our social infrastructure possible. What’s a huge shame is that many of them cannot afford to live in the place from which they derive their livelihood. There are many reasons for this state of affairs. The main one, to my thinking, is the desirability of our quality of life, which, perversely, these people are key. It creates demand that prices out the people on whom our social infrastructure depends.

Hence, the long lines of traffic heading in every morning from Ventura, Oxnard and points beyond, and the long lines heading out every evening.

Since I’ve been harping on this subject for years, and have no easy answers and no simple solutions, I’ll digress for a moment to illustrate why this debate matters. Stay with me.

Basic training at Lackland Air Force Base just outside San Antonio, Texas was the roughest period of my life, at least up ‘til then. I was a raw scrub recruit from a small farm town and the whole structure of it was alien to my unsupervised routines as the fifth of six children who received one of the best parenting styles yet devised — benign neglect. It may be the best method for most situations, but it left me ill-prepared for its opposite, a 10-week military boot camp. Worse, I had generations of veterans as role models — brave, stoic men and women who did their country proud and I just didn’t feel up to it.

In fact, I was set back in boot camp two weeks and it was made clear that any further failed inspections or infractions and I’d be on the long bus ride back home, head hanging low in shame. I wouldn’t be just letting myself down, but all the soldiers my lineage going back to the Civil War. I could just picture my misery, and let that motivate me to do better.

There was a huge basewide exercise, war games of the sort that were common during the Cold War. I was on guard duty for our barracks with clear instructions that whoever approached had to show the proper badges and passes according to their rank.

It was shift change, and the airman who was replacing me had barely put on his own badge when our head drill instructor, a bantam-weight African-American master sergeant with impeccable military bearing, loudly knocked and insisted on being let in, even though he was (deliberately) showing the wrong access badge. My replacement was on the verge on opening the door, until he saw my gesture to stop. The master sergeant then presented the proper badge, was let in and immediately got right up under my chin and demanded, “Did you tell him not to let me in?” Caught off guard, I said “No sir, no sir!” He then stood back, shook his head in disappointment, and said, “Bradigan, is that who you are?” I felt awful, and tried some version of “Sir, I didn’t actually tell him, I just gestured.” It was my “depends on what the meaning of is is” moment. It stings to this day.

He then ordered me to follow him around as he inspected the barracks and gave me a stern lecture about integrity and honor and owning up to life’s demands with strict accountability. The fact that he did it in a normal speaking voice, after hearing him shout for the past month, made it seem all the more consequential. It was the longest 20 minutes of my life and I had nothing to say in my defense. Even though I had done the right thing in denying him entry without the proper credential, I had gone about it in the wrong way. Somehow, that was far worse.

It took me years to realize that he wouldn’t have bothered to lecture me if he didn’t think it worth his while, that maybe I was worth rescuing. He certainly didn’t lecture the other airman who was about to commit a serious security violation. Somehow, even with his stinging rebuke echoing in my ear, my final weeks of boot camp passed uneventfully and I spent the next six years having experiences of a lifetime all over the world. He had done his job.

Most of us have these drill instructors either internal or external to help keep us on track. If we are to solve the central issue of Ojai — that our sense of community is diminished when the people on whom we depend are distanced by our lack of affordable housing — it will take tough criticisms of who we are, and where we are going. We must demand integrity and accountability from ourselves before we demand it of each other as we enter into the debate.

There are efforts afoot to get us all on the same page. There will be updates soon from the Carnegie Mellon School of Transition Design, which first came to Ojai in the ashy aftermath of the Thomas Fire, when it seemed that Ojai’s economy was done and dusted. The economy’s an important part of it, finding a path to prosperity that is as inclusive as possible and protects our environment and way of life. But when we think of our community’s future, we have to figure out a way to bring home those teachers and hospitality workers and police officers.

We tend to sort Ojai’s issues into separate compartments; housing, traffic, air quality, economy, water. But creating affordable housing goes a long way to solving many of those problems at once.

I imagine my former drill instructor as a stand-in for the teachers and cops who enrich our community, and the thought that people who bring such value to our lives couldn’t afford to live in Ojai makes me feel like we’ve done them, and ourselves, a disservice.

Leave A Comment