FEATURE | By Kit Stolz

Marcel DuChamp, Beatrice Wood & The Making of the Art World

Beatrice Wood & Marcel Duchamp

Beatrice Wood, the artist and icon, still lives on in the hearts and minds of Ojai residents, despite passing away nearly 25 years ago. By contrast the larger world — in this case, London, New York and Hollywood — seems to forget about and then rediscover Wood’s extraordinary life and work every quarter-century or so, and then, almost invariably, tries to put her into the movies.

Last time around, in 1997, it was a prominent Hollywood writer and director, James Cameron, who, while casting about for an appealing female lead for a grand love story, encountered Wood’s 1985 autobiography — “I Shock Myself” — and loved it. Cameron ingeniously rewrote Wood’s impetuous artistic rebellion in Paris in the pursuit of love into an epochal trans-Atlantic journey that, despite its tragic conclusion, won young Kate Winslet an Oscar. Cameron made Beatrice Wood’s character arc in effect the star of one of Hollywood’s most successful movies, “Titanic.”

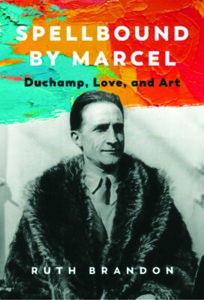

Twenty years later, an English novelist and historian, Ruth Brandon, while pursuing a different story — involving the brilliant but confounding French conceptual artist Marcel Duchamp — came across the unpublished diaries of Wood and that of her first lover Henri-Pierre Roché. Brandon, a prolific author whose work often has a feminist edge, could not resist the emotional, outspoken Wood. In a book published this year and originally intended to focus on the charismatic Marcel Duchamp and his circle, called “Spellbound by Marcel: Duchamp, Art, and Love,” she wrote mostly about Beatrice Wood.

“I was drawn to her story because it’s a good story,” Brandon said, on a Zoom call from London. “We were planning to tell the story of Duchamp and I came across these diaries, of Wood’s and of Roché’s, and it’s just fantastic. It turned out to be a story, in her case, of someone who refused to accept what she was supposed to be like, which was a respectable young lady of the middle class.”

Brandon first wrote the idea into a screenplay with a director friend for a film project about the charismatic Duchamp and the 2017 centennial of his infamous conceptual art piece, “Fountain,” a urinal which he scandalously displayed as a “readymade” sculpture. But although “Fountain” in 2004 was declared the most influential work of art in the 20th century by a panel of 500 experts, Brandon thought the lives of the rebel artists and the women who loved them, such as Wood, far more compelling than their abstract art. Wood in her youth was a romantic, trapped in between two divergent but equally cold-hearted worlds: The wealthy high society of New York, and the startling and sometimes sexual provocations of Duchamp and the Dada movement. When the movie project about “Fountain” fell through, Brandon wrote a story of lives on the artistic edge into a book that has made a considerable splash.

“When I read her diaries, alongside Roché’s, I realized that this was going to be a book about three intertwined lives, and also that it was going to be an essentially feminist book, with her at its center,” Brandon said. “The men had total freedom to live as they pleased and make careers, or fail to make them, and the women, even the most emancipated, had really very little.”

“When I read her diaries, alongside Roché’s, I realized that this was going to be a book about three intertwined lives, and also that it was going to be an essentially feminist book, with her at its center,” Brandon said. “The men had total freedom to live as they pleased and make careers, or fail to make them, and the women, even the most emancipated, had really very little.”

Brandon’s film project concluded at a deeply unhappy moment in Wood’s life, after the betrayal she suffered at the hands of her first lover. She ran away to Canada, where she had been offered a part in a play, and where she hoped to find a future as an actress after Roché, a seducer — or “sex addict” in today’s terms, as Brandon convincingly argues — broke her heart.

To Roché, deflowering the virginal Wood counted as a sort of exotic treat. After he seduced her in 1917, he continued to bed many other women, even while sleeping with her. When one paramour, Alissa Franc, a journalist friend who had introduced Wood to Duchamp’s circle months before, warned Wood about him, and finally told Wood of Roché’s own dalliance with her, a shocked Wood fled. She described the scene to her diary in a few teary lines. After a last embrace, she kissed Roché goodbye and went home shattered, writing in her diary that “I never suspected the world could be like this.”

In her 1985 autobiography, “I Shock Myself,” Wood mentions that years later she reacted artistically by creating clever and often amusing little bordellos out of clay. She wrote:

I love to do bordellos. I realize the reason I do is that they are a release from my shock over discovering Roché had slept with so many women. Even though I’d read Dostoevsky and Tolstoy, I never dreamed such a thing existed in the world. It was a great shock. I still haven’t gotten over it.

Wood married twice, and divorced twice, and never found romantic fulfillment. “I never made love to the man I married, and I never married the men I loved,” she bluntly admitted in her autobiography. But after finding steady work as a potter in midcentury Los Angeles, and then settling in bucolic Ojai, Beatrice Wood found a different life in art and spirituality, and her work — and her sly, provocative character — emerged and flourished. When asked in her nineties the secret of her longevity by a reporter in San Francisco, Wood declared that she had “two great joys in life — chocolate and young men,” a line that she often repeated, with variations.

In Ojai today, her past among the artists of the Dada movement in Paris and New York is little known or remarked on, but her bold, provocative character remains as beloved and as celebrated as ever.

Alasdair Coyne, the organic gardener and wilderness activist, cared for the gardens around Beato’s home and studio — now the Beatrice Wood Center for the Arts — for many years in Upper Ojai, and came to know her well. Looking back, he treasures that time in her company.

“She was always gracious and friendly, with a lively, salacious wit,” he said, adding that “Beato said she would have hired me even if I was a lousy gardener because of how I looked without a shirt on.”

His admiration and affection for Wood was echoed wholeheartedly by her many caregivers and studio assistants still present in Ojai and Upper Ojai, including caregivers such as Karin Dron, Adriana Goddard, and Liz Otterbein, and studio assistants Lola Long and Nanci Martinez.

Otterbein, who grew up in France and spoke French with Wood when she helped take care of the older woman late in her life, considered Wood “a teacher.” Otterbein, who cared for her mostly at night, would rise with her in the morning, and remembers fondly her morning routine.

“She was always considerate of other people and always asked me how I was in the morning,” Otterbein said. “And the second thing she would do, was to go to the window, and look out. “‘Oh, look, the dogs are out, or something like that,” she would say. “And then she would say “Good morning, cactus,” to the cactus that stood outside the window. That was a practice of appreciation, of consideration, that I tried to bring into my life.”

Karin Dron, who also worked as a caregiver for Wood, recalls how Wood’s “salacious wit” could startle people. Her late husband Boyd Dron met Wood at a young age, she said.

“One time Boyd was at a party when he was seventeen,” she said. “And Beatrice came up to him and said, “I like young men.” Boyd was very very shy at that point, but I think he made a decision at that moment to get over his shyness!”

Dron links Wood’s “sense of play” in her life and in her art to her great success late in life. She says, as did Otterbein, that Wood was astonished at how successful she became. Otterbein recalls Wood looking at one of her famous pieces of “luster ware” pottery, and turning it over to see the price tag, and making a face at the high price. Dron recalls Wood describing herself, despite acclaim and many museum shows, as a “naive craftsman.”

Nanci Martinez, who worked closely with Wood for five years, archiving her collections and curating exhibitions as an art dealer and gallery owner, sees Wood’s self-declared naivete as a conscious choice. She added that Wood’s humor, although great fun, could mislead people into overlooking her spirituality and her generosity. She points out that Wood came to Ojai in large part because of her interest in the philosopher Krishnamurti and the Theosophical movement founded in part by his supporter Annie Besant.

“Beatrice came from a very affluent family, and stepped out on her own very bravely when that was not what young ladies did,” Martinez said. “She struggled through a great deal of her life living very modestly, and when her work started selling, she shared very generously, always giving to the Red Cross and many others. One of my jobs was to let her know how all the people who worked for her were doing, and to let her know if they needed help. She paid dentist’s bills and for education, and if she wasn’t able to give cash, she would give a gift of her pottery, which could be sold for $5,000. Those kinds of things were foremost in her mind, not how can I get more attention for me.”

Martinez looks back on her time working with Wood with fondness and great respect.

“The best thing about working for Beatrice was that there was only one way to do things, and that was the right way,” she said. “She faced this moral question a lot, such as: are we going to cheat a little bit on the taxes? She and I would face this question together, and she would often ask when we had an issue with this or that or in the studio, okay, let’s play ‘the highest good game.’ What is the highest good here? For everyone involved?”

Martinez added that after Wood died, her work — which had been carefully managed by a Los Angeles gallery owner and art historian named Garth Clark — flooded the market.

“She gained a lot of recognition and was highly collectible up until the end of her life, but after she passed away, a deluge came on to the market,” Martinez said. “eBay was hitting and the whole art market was changing and at that point supply and demand came into play, and with a lot of supply the value of her work went down a bit.”

This commercial fact was noted, surprisingly, in a remarkably appreciative review of “Spellbound by Marcel” by perhaps the premier art critic in the country, Peter Schjeldahl of The New Yorker. Although he complained that the book was “gossipy,” he raved about Beatrice Wood herself, describing her “élan as legendary,” adding that “Wood seems to me a singular, wild-card creative personality of the twentieth century.”

He even declared — startlingly for an admired critic — that he thought the market for her luster-ware ceramics was underpriced, declaring that “the present market … though active, is less than robust …This signals a lingering, blinkered bias of art collectors against craft mediums. These things are terrific.”

Kevin Wallace, who manages the artistic and cultural legacy of Beatrice Wood at her Center for the Arts in Upper Ojai, said that the review may have sparked a revival of interest in her work.

“The day after that review came out, I had a woman from New York City call me,” he said. “She had read the review and fallen in love with Beatrice Wood and bought a $3,000 piece before I’d even had a chance to read the review. We’ve had people coming up saying “I read the review and I wanted to come see for myself.” I do think this will create some resurgence of interest, but Beatrice Wood was not just an artist but a personality. So many people come to visit the center and say she’s their hero.”

Wallace has lived and worked with Wood’s legacy for years, and has some ideas about why she appeals.

“From the time she was a young girl she knew she would run away from home,” he said. “Her entire journey was a search for herself, and that includes Theosophy, Krishnamurti, and her great loves. It’s all part of her search for true happiness and a true becoming. When she came to Ojai she found who she was meant to be in the world, and the last years of her life, from her 80s onward, were the happiest years of her life, and I think that is remarkable. I think she and Ojai were meant to be together — call it destiny, call it cosmic, call it what you will, but it seems to have been written in the stars.”

Wallace, who read “Spellbound by Marcel” shortly after its release, notes that the book has been criticized by art historians, primarily for flubbing certain details about secondary characters such as Duchamp’s close friend Man Ray. He suspects that Beatrice Wood herself would consider it an invasion of her privacy, but he still sees its value.

“I think the book was written not to be a documentary of 20th century art. It’s not really about the facts, it’s closer to historical fiction, and I think it’s written in such a way to make it clear this would be a really great movie,” he said. “I’m surprised no one has done that yet.”

For Ruth Brandon in London, Wood was the great survivor of the charismatic but cerebral Marcel Duchamp’s artistic rebellion, the rare American woman artist of the era who became “not just financially independent, but famous in her own right.”

Nancy Martinez sees Beatrice Wood as irresistible, and thinks it fitting that Wood, although known in art history as a secondary figure in the highbrow world of Dada, would go on to become famous around the world, among millions of people who have never heard of Marcel Duchamp, as a character in her own right.

“My little soundbite is that it wasn’t her work, it was her life that was her greatest masterpiece,” she said, and then added a little story from Ojai to illustrate the point.

“Beatrice originally thought James Cameron was writing a story about Duchamp,” she said. “She gave her permission for him to use her story in his movie, and after ‘Titanic’ was released he came back to visit and give her a boxset of the movie. I showed him and Gloria Stuart [the actress who portrayed Wood’s character in the film] around the studio. It was a wonderful visit, but Beatrice was in the next room and didn’t hear everything, and when she had a minute she grabbed me and took me aside and said, ‘You have to clean this up! I wasn’t on the Titanic! He’s written me into this story, and how am I going to burst his bubble? Oh my goodness what am I going to tell this poor man?’”

Leave A Comment