FEATURES | By Mark Lewis

Ojai Pilgrims

Krishnamurti and Annie Besant

When England’s Puritans set sail for the New World, they hoped to establish their version of Utopia there, as a shining example for the rest of humanity.

“We shall be as a city upon a hill,” their leader John Winthrop said. “The eyes of all people are upon us.”

Three centuries later, another English spiritual leader embarked upon on a similar pilgrimage to America, but she landed in Ojai rather than Massachusetts. Her name was Annie Besant, and she was president of the Theosophical Society, a group which sought to synthesize the religions of East and West.

“We desire to form on this land a Centre which shall gradually grow into a miniature model of the New Civilization,” she wrote in The Theosophist magazine in January 1927, during her first and only visit here.

Besant had been guided to Ojai by her protégé, Jiddu Krishnamurti. He had stumbled across the valley five years earlier, fallen in love with it, and acquired a home here, with Besant’s help. After Krishnamurti put down roots, the Krotona Institute of Theosophy followed suit, moving to Ojai from Hollywood. Then Besant arrived, and she too was smitten.

“One of the beauty spots of the world is the Ojai Valley in California,” she wrote in The Theosophist. “Mountains ring it round; it has remained secluded till recent times, and is still but sparsely inhabited. … Such is the setting for the cradle of the New Civilization in America.”

History records that her plans were thwarted when Krishnamurti renounced the messiah role she had assigned to him. But a new exhibit at the Ojai Valley Museum takes a different view. (Disclosure: I was among the exhibit’s creators.) The exhibit — titled “Legacy: Krishnamurti and Ojai” — highlights the many iconic institutions that, in one way or another, grew from seeds planted a century ago by those Theosophical Society pilgrims. If Besant & Co. had never set foot here, Ojai as we know it today would not exist.

The story begins in London in 1889, when Besant, a famous labor and women’s rights activist, was asked to review Helena Blavatsky’s book “The Secret Doctrine,” for The Pall Mall Gazette. After reading it, Besant sought out Blavatsky, the co-founder of the Theosophical Society, to delve further into the subject. Later that year, Besant declared herself a Theosophist. She moved to India, and by 1905, after Blavatsky’s death, Besant was president of the society.

In 1909, she proclaimed Krishnamurti the next World Teacher, the messiah figure whose coming Blavatsky had prophesied. He was only 14, but he was game to try. She sent him to London to be educated along English lines, and his younger brother Nityananda went along to keep him company.

Fast-forward to Sydney, Australia, in the spring of 1922. Krishnamurti and Nitya had accompanied Besant there to attend a Theosophical Society convention. When Nitya suffered a recurrence of his tuberculosis, Besant decided that the brothers should travel to Switzerland to consult Nitya’s doctor, a TB specialist. They booked passage on a transpacific steamer from Sydney to San Francisco, intending to cross the U.S. by train and then board another steamer for Europe. But when they arrived in San Francisco, fate diverted them to an unplanned destination.

The initiative came from Albert P. Warrington, head of the Krotona Institute of Theosophy, which he had founded in Hollywood a decade earlier. As it happened, Warrington knew a Theosophist who owned a weekend home in Ojai, then a well-known health resort for people with lung problems. Warrington suggested that Nitya might benefit from a relaxing stay there, before continuing on to Switzerland. Intrigued by America, and wanting to see more of it, the brothers accepted his offer. They traveled by train to Ventura and by automobile to Ojai, arriving on July 6. Warrington had arranged for them to share a rustic cottage amid the pine trees of the East End. They loved it, so much so that Besant arranged to buy the Pine Cottage for them, along with a nearby ranch house. (The brothers dubbed it Arya Vihara, Sanskrit for “Noble House.”) Alas, Nitya found no cure in Ojai; he would succumb to his disease within three years. But Krishnamurti would maintain a home here for the rest of his very long life.

With the future World Teacher now established in Ojai, Warrington decided that this was just the place for Krotona, too. In 1924 he moved the institute from Hollywood to a 118-acre ranch property atop a hill just south of Meiners Oaks. That set the stage for Besant herself, who came to Ojai in October 1926 to see what all the fuss was about. Soon, she too was a convert.

Ojai, she announced, would become a model Theosophical community, dedicated to education, the arts, and general cultural uplift. To get the ball rolling, she purchased 465 acres in Upper Ojai, a property she dubbed Happy Valley. She created the Happy Valley Foundation to oversee its development.

She also bought 175 acres near Krotona, including an inviting oak grove suitable for public gatherings. Shrewdly, Besant also bought the local newspaper, The Ojai. Theosophists began flocking to the Ojai Valley, buying lots in the recently subdivided Meiners Oaks town site, or in the new Siete Robles subdivision east of downtown Ojai.

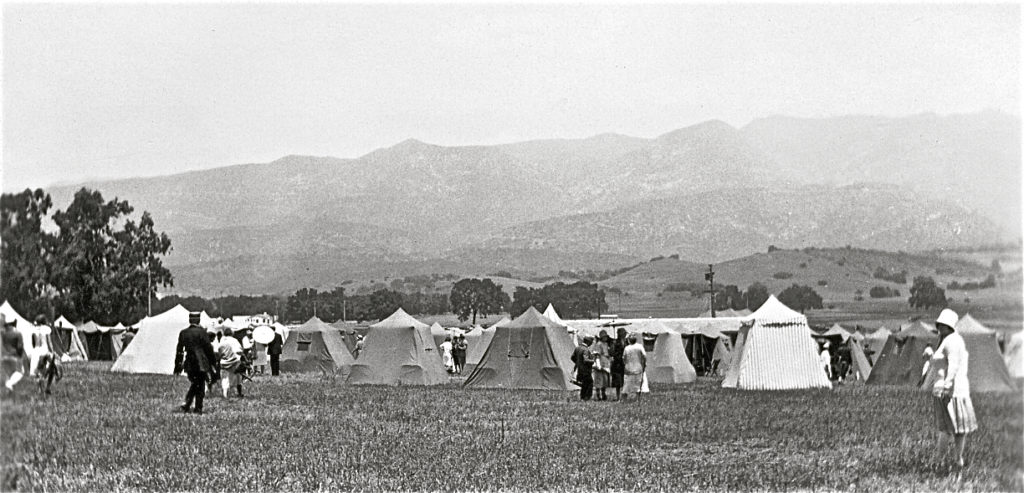

In April 1928, a vast tent city arose in Meiners Oaks to house the 1,200 people from all over the world who came to hear Krishnamurti speak for the first time in the Oak Grove. This Star Camp event was repeated a year later. It appeared as though Besant’s vision was on the way to fruition, and Ojai was destined to become the mini-Mecca of a major new world religion. Then the World Teacher stunned Besant by submitting his resignation.

“I maintain that truth is a pathless land, and you cannot approach it by any path whatsoever, by any religion, by any sect,” Krishnamurti announced in October 1929. “I desire those who seek to understand me to be free; not to follow me, not to make out of me a cage which will become a religion, a sect.”

That was the end of Annie Besant’s dream of Ojai as a Theosophist utopia. Or was it? The Theosophists never left. Krotona is still here today, as is Taormina, the nearby neighborhood founded in the 1960s as a Theosophist retirement community. (You no longer have to be retired or a Theosophist to live there.)

Happy Valley remained undeveloped until the 1970s, but the Happy Valley Foundation never gave up on Besant’s vision. Today this property is host to the Besant Hill School of Happy Valley, the Beatrice Wood Center For the Arts, and the Ojai Foundation.

Krishnamurti never really left Ojai either. After renouncing the messiah role, he became a globe-trotting philosopher, sharing his thoughts with audiences in Europe and India — and in Ojai, where he continued to give talks in the Oak Grove. In 1969, he established the Krishnamurti Foundation of America to preserve and disseminate his teachings. In the 1970s he founded the Oak Grove School. He died in Ojai in February 1986 at the age of 90, but remains a presence here today thanks to the foundation and the school – and to the many people he drew here.

Krishnamurti did not want followers, but he got them anyway, and thousands of them followed him to Ojai. Those still active here today include the environmental activist Alasdair Coyne, and Carol Smith, a former mayor of Ojai.

Also among those drawn to Ojai in the 1970s by their interest in Krishnamurti was Tom Krause, who worked with the philosopher while serving on the board of the Krishnamurti Foundation of America and the Oak Grove School while his children were students there. Krause eventually broke with Krishnamurti but remained in Ojai, where he founded Behavioral Science Technology Inc. (BST) and currently serves as chairman of Ojai Chautauqua, president of the Agora Foundation, and on the board of Thomas Aquinas College.

Many folks who never fell into the “Krishnamurti devotee” category nevertheless found him interesting enough that they came here to hear him speak in the Oak Grove — and, as a result, they discovered Ojai, fell in love with it, and eventually moved here. This group includes Phil Harvey, who founded the Ojai Community Chorus and the Ojai Camera Club (now called the Ojai Photography Community); Bill Weirick, now a City Council member; and Ellen Hall, another former mayor, who co-founded the Ojai Valley Land Conservancy, and has served at various times as head of the Oak Grove School, Meditation Mount, the Green Coalition and the Ojai Valley Museum.

In addition to founding the Oak Grove School, Krishnamurti also was a co-founder of the Besant Hill School (originally called the Happy Valley School). Both schools, over the years, have attracted many interesting people to Ojai, either as students, parents or teachers. Among them is Sergio Aragones, the famous Mad Magazine cartoonist, who first came here to hear Krishnamurti speak, then moved here in 1982 so that his young daughter could attend Oak Grove. Her school days are long over, but Sergio is still here.

Then there are those notable Ojai natives who are descendants of pilgrims, such as the musician Martin Young, whose parents Peter and Heather Young were drawn here from England in part by their affinity for Krishnamurti. (Heather was a founding member of the Ojai Studio Artists group.) Another example is the artist Teal Rowe, whose Theosophist maternal grandparents, Walter and Daisy Hassall, came here from Australia.

All these people, and many more with similar backgrounds, have made their marks on Ojai. None, arguably, would have come here or been born here if Krishnamurti, Warrington and Besant had not come here first.

Besant only came to visit; she left after seven months, and never returned. But it was she who laid out the vision, approved the plan, and bought the land. And it was she who issued a clarion call to Theosophists around the world, many of whom would end up in Ojai. They had never heard of the place before Besant wrote her Theosophist article in January 1927, unveiling Ojai as the cradle of a new civilization. She wrote the article while staying at Arya Vihara on McAndrew Road. (It’s still there, but now known as the Pepper Tree Retreat.)

“Let me then sketch what are to be the ideals of our community,” she wrote. “The bodies of the members should be developed into beauty by healthful exercises, games, sports of a non-brutalizing character, by purity and simplicity of daily life, by living the open-air natural life rendered possible by the climate, by the influence of the exquisite beauty of Nature surrounding them and by beauty in their homes, and refinement in dress, speech and manners.

“…The emotions that find expression in art and in the enjoyment of beauty, in music, painting, sculpture, should be diligently cultivated. Their minds must be trained by study, by discussion, by strenuous thinking, and they must add to education, culture.

“… Among our institutions must be, in addition to the school — expanding later into a college — a library, a club, a temple for worship and meditation, an art center, a Co-Masonic Lodge, a theater, playgrounds for adults (in addition to that of the school for children), and any others for which there is a demand, as funds permit. These should attract visitors of intellectual or artistic merit, men and women of originality and special type of ability, who might find inspiration in the atmosphere of the community and the beauty of the valley ….”

Arguably, Besant’s vision for the Ojai Valley has come to pass. Apart from the Co-Masonic Lodge, some version of every item on her “institutions” checklist can be found here today, and they do indeed attract visitors “of intellectual or artistic merit” who find inspiration in Ojai’s vibrant culture and natural beauty. This community in 1922 was not known as a haven for artists, conservationists, intellectuals, and spiritual seekers. That changed with the coming of Krishnamurti and the Theosophists. Over the course of a century, they — and their biological and spiritual descendants — wove themselves into the fabric of this community, and created the Ojai we know today: artsy, activist, green-minded, intellectually curious, and prone to New Age enthusiasms.

Annie Besant died in 1933, at a time when her Ojai project apparently lay in ruins due to Krishnamurti’s break with Theosophy. But she had foreseen from the beginning that there would be obstacles along the way.

“Our first efforts may be clumsy and feeble,” she wrote, “but none should be discouraged by this inevitable fact. ‘Hitch your wagon to a star,’ said Emerson, and we shall follow his advice, however far off the star may be; it will ever shine over us, inspiring and guiding us.”

Like the Pilgrims of New England, the pilgrims of Ojai did not accomplish quite what they set out to do. Nevertheless, they too created something worthwhile, and their legacy endures. Since Besant liked to quote Ralph Waldo Emerson, we will quote him here, slightly paraphrased:

“She builded better than she knew; the conscious stone to beauty grew.” ≈OQ≈

Leave A Comment