FEATURE | By Robin Gerber

From Whale Rock To Solar Punk: Public Art in Ojai

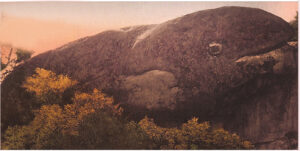

Whale Rock

I’m standing in a small clearing staring up in wonder at a life-sized rock of a whale with her baby nestled at her side. Whale rock is thousands of years old, set in a rocky outcropping now on private land overlooking the Ojai Valley. Could Whale Rock have once been “public art,” a place where First Nations Chumash people gathered for ceremonies? A place that stimulated dialogue, thought and wonder? “It’s possible,” says Chumash elder Julie Tumamait Stenslie. “The Chumash likely held ceremonies there for the full moon, new moon, solstice, comets streaking in the sky or vision quests.” Today, we think of public art as statues of famous people, sculptures or murals in public or private spaces that are accessible to all of us. The emphasis is on the art being in public view. Think Ted Gall’s huge steel horse at the Y intersection, Sylvia Raz’ Early Bird Shopper in the Arcade Plaza, the wrought iron patio gates behind the Art Center, or the Trimpin Arch at Libbey Bowl that rewards visitors who walk through with percussive bursts of music.

But what if we emphasized art that speaks to community values, needs and ideas? Static creations, even interactive ones, are narrow examples of an expansive and ever-changing idea of public art. Kristopher Wallin, who founded Tierra Sol, an art and resiliency project, says, “public art can align communities toward issues like equity and climate. This can accelerate policy change.”

Murals are one example of public art meeting community ideals. Dr. Tiffany Morse, Superintendent of Ojai’s public schools, had the idea for a mural on the side of the District’s Montgomery Street building. She turned to Ray Powers who put together a team, including mural artist Lisa Kelly and 25 students. The completed 30-by-14 foot mural depicts the Ventura river rich with plants and wildlife under Ojai’s famous pink sky. It is a future vision of the local watershed after the controversial Matilija Dam has been removed.

OUSD mural

“Enlivening the Matilija Watershed,” is the mural’s title, but it is enlivening the thinking of the community about its relationship to the natural environment and the critical role of water. The mural is also interactive with a QR code that explains elements of the scene. Paul Jenkin, who has worked for decades to remove the dam says, “Art is such a powerful tool to illuminate things in front of our eyes that we don’t see.” The dam itself had protest art of a scissors cutting a dotted line down its wall. The iconic image, turned into bumper stickers, reminds people of the movement to remove the dam.

New technology in clean energy is allowing public art to evolve into “sustainable art.” For example, custom laminates and painted thin films can be placed on solar panels creating new kinds of public art. The Ojai Unified School District will soon be leading the way with new solar installations around town that will carry artistic designs and possibly distinctive architecture, some of which may be created by students and the community. These works of art will enrich Ojai’s community narrative about sustainability, while generating renewable energy.

New visions of public art also include performance. Tierra Sol’s solar powered, zero waste event this summer used the valley view from the Ojai Retreat as an inspiring backdrop for a profound event including music and poetry. As Kristopher Wallin said, “The arts function as a needed catalyst for a Renaissance of humanity’s relationship with our planet. We need to be activated and inspired through a deeper engagement that the arts provide.”

Tierra Sol event at Ojai Retreat

Tierra Sol has also brought the Land Art Generator Initiative to Ojai. This group has worked around the world designing renewable energy infrastructures that are also beautiful and culturally relevant. This focus on renewable energy that pleases the eye blends perfectly with Ojai’s race to resiliency and art-focused culture.

Ojai city government began taking an active role in public art thanks to two brilliant and visionary women who created Ojai’s first arts advisory council in the 1990s. Nina Shelley served on the City Council and as Mayor in her nearly two decades of service to Ojai. During World War II, she was in the first group of women to serve in the Marines after getting a Fine Arts degree in college. Shelley enlisted Vivika Heino, the renowned ceramicist, to convince the City Council that public art was important to the City’s civic and cultural life. The arts council they created led to the present day Arts Commission.

The City began working on a public art ordinance in 1997, but it took until 2002 for glass artist Susan Amend, Maudette Fink and artist Karen Lewis to draft language that the City accepted. “Sitting together on the Arts Commission, we tried to base our drafts on other cities’ ordinances, but it was a lot of work because we had to shape it for our unique city and valley,” Amend recalls. Lewis remembers Fink spearheading the effort at a time when the City had a great deal of building and remodeling going on. Fink had run a museum in Orange County and saw the opportunity presented by construction in the Arcade Plaza, Cluff Vista Park, Bryant Street and other locations. Ojai is an arts city, and the City Council finally approved “2% for the arts,” an initiative tied to development that created both a public art fund and installations of public art on private land. Similar programs are in place in many California cities large and small, as well as cities nationally.

Trimpin Sound Arch

Ojai’s public art provides people the experience and the pleasure of seeing art in their daily routine and increases their quality of life. Ojai resident Corrina Wright, who has been the director of numerous art galleries, points out that public art also “breaks the traditional barriers of seeing art. People don’t have to go to institutions to see art, it’s right here in their day-to-day lives.”

But is it enough for public art to be pretty and pleasant? Can we use art to shine a light on public issues like affordable housing, fire readiness, and racism? What if city government engaged artists to help illuminate social issues, spark dialogue, educate and support community consensus building? Barbara Hirsch, longtime arts curator and collector says, “It used to be that you commissioned an artist to do a piece. It was about art for art’s sake, but now art is about ideas, community, place-making and presenting larger ideas and ideals.” Hirsch is right.

The definitions for percent-for-art programs are expanding, along with the recognition that art is a powerful force for social change.

One vision of the future of public art is a movement called “Solarpunk” which imagines a world fueled by renewable energy. In that world, artistic expression harkens back to nature with inspiration from Art Nouveau and handcrafted work. Solarpunk is egalitarian, anti-everything from consumerism to racism, sexism and war. In a Solarpunk future, Whale Rock might once again be public art. It would be a place that anyone could visit. Standing before that magnificent expression of earth’s mysteries, humans would find inspiration for facing what lies ahead.

Good day. You failed to recognize the amazing hand painted electrical boxes commissioned by the Ojai Arts Committee in 2020. Three great and well established local artists were nominated to beautify ojai. Leslie Marcus (electrical box on north ventura avenue across from Mob Shop) Carlos Grasco’s ( electrical box located in Libbey Park by children’s playground) and Dominique ( two electrical boxes by the Libbey tennis court’s bleachers). The “official ribbon cutting ceremony” was canceled due to Covid. I feel The Ojai Art Commission, and these artists deserve recognition for their exquisite art work and contribution to the community. I suggest you explore these artful wonders, photograph them and acknowledge credit to The Ojai Arts Commission, and the hard working artists that took pleasure in giving back and beautifying our community.

“But is it enough for public art to be pretty and pleasant? Can we use art to shine a light on public issues like affordable housing, fire readiness, and racism? What if city government engaged artists to help illuminate social issues, spark dialogue, educate and support community consensus building? Barbara Hirsch, longtime arts curator and collector says, “It used to be that you commissioned an artist to do a piece. It was about art for art’s sake, but now art is about ideas, community, place-making and presenting larger ideas and ideals.” Hirsch is right. ”

On a personal, (and somewhat political), note: I titled my “painted box” On North Ventura Avenue “GRATITUDE”. After residing in Ojai for over 25 years, I have been asked beyond numerous times by visiting tourists, “What’s there TO DO, here in Ojai”. Where I would reply ~ “look around you, take a walk and appreciate the simply yet spectacular and unique beauty”. I have received so many compliments on my painted electrical box; locals and visitors who said my painted box made them smile, gave them joy, lifted their spirits after a hard days work……. Shifted their mood from tired and worn to grateful for the small wonders in our community. Mental health is a serious growing issue, with no barriers of age, race, sexual orientation, or religion. If my public art installation, commissioned by The Ojai Arts Committee, helps put a smile on peoples’ faces, shifts their outlook, even a little, from despair to hope, I feel as though my small contribution was worthwhile, with integrity and intention beyond “pretty”. “Art Saves Lives” as some of us ‘old schooler’ have bumper stickers on our vehicles. The intention of GRATITUDE, beyond its pleasing beauty, is a reminder to all of us: to stay “present” ~ there is unlimited potential in “being” rather than “doing”.