ENVIRONMENT | By Misty Volaski

Permaculture’s Path to Sustainable Future

This past Thursday, leaders of eight local nonprofit groups dedicated to environmental conservation and preservation met at Ojai Retreat for a panel discussion, “Stewardship in the Ojai Valley,” led by Andy Gilman, director of the Ojai Chautauqua.

Here is a story about one local man’s effort at stewardship first reported in the Ojai Quarterly’s Summer 2016 issue:

As new islands and old schoolhouse foundations emerge from a rapidly shrinking Lake Casitas, the power and importance of water — and lack thereof — is particularly poignant to Ojai Valley residents.

Is there a better way to do this? Can we save ourselves, rewrite our futures and avoid the seemingly inevitable progression of climate change?

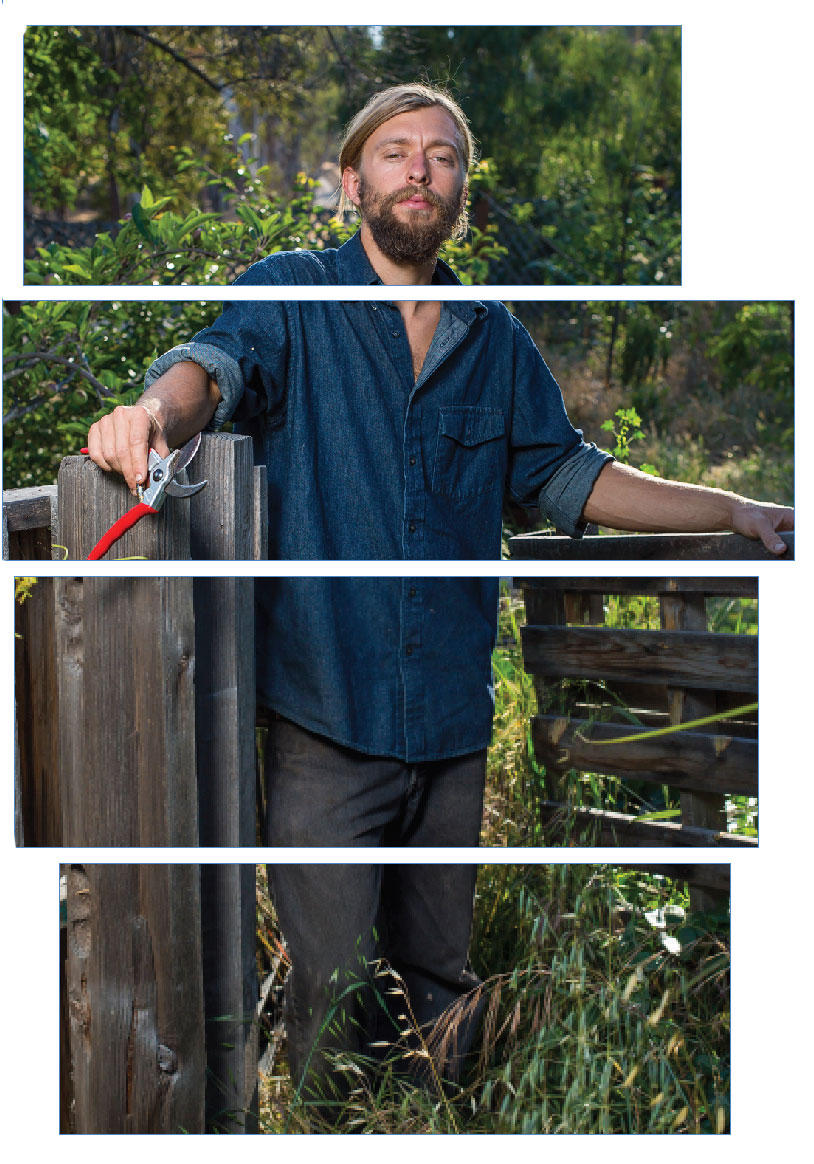

Connor Love Jones thinks we’ve got a real chance. With his East End Eden farm as a model, he’s utilizing ancient knowledge, modern science and a hefty dose of logic — along with some good old-fashioned muscle — to create a truly sustainable living environment.

It starts, he says, with “a subtle change in the design and management of the water resource. Instead of paving, piping and polluting it, sending it away as quick as possible, we have to change the standard narrative of water management in our culture.”

City planning over the last few centuries has attempted to channel storm water out and away from communities. But in the 10,000-odd years humans have inhabited the Ojai Valley, myriad rivers and creeks flowed year-round. Swampy marshlands near Nordhoff High School and Mira Monte, among others, would capture the rain and let it settle back into the water table.

In recent years, cities and municipalities have started to catch on to the fact that these areas are necessities to a healthy ecosystem. Hence, the birth of the artificial bioswale, such as the one near Meiners Oaks Elementary School. These relatively simple landscape features are being constructed to redirect water from those wasteful drains and into specially-designed catchponds. These slow the water, spread it out over thirsty land, and allow it to slowly sink back into the ground. As it sinks, it is filtered through rocks, soil and vegetation — all of which help remove pollutants — before it gradually makes its way back into the water table.

Connor Love Jones has implemented similar processes — and far more — at his East End ranch. Working with, rather than against, the principles of nature have allowed him to design a “food forest” that incorporates about 150 edible species into one acre.

“Diversity,” he asserts, “is resilience.”

At first glance, it doesn’t look like much. But the tangled mass of trees, shrubs and grasses — along with the goats, pigs, chickens and even the 18-year-old tortoise — are all carefully chosen and placed to get the most out of each species. “Everything here is either food, medicine, fuel or fiber,” Jones says. And water is the foundation for it all.

Any rain that falls on the property’s southern hill is channeled into a pipe and down into the food forest. A hand-dug channel weaves in and out of the forest, further capturing rainwater. Five bioswales slow and sink the rainwater, providing a deep drink for the plants and trees.

The result? A catchpond a few dozen yards to the east, which gets more than 10 feet deep after just two inches of rain (it also offers a home for minnows and catfish).

The property’s water well isn’t running dry the way most are in this area. In fact, it’s thriving.

“We’re building our own shallow aquifer,” Jones says.

As he walks through the land, he points out individual plants and describes their respective roles. The tortoise feasts on the tall grasses and weeds, clearing space for more food and leaving behind quality fertilizer. The goats will do the same. Nearby, the honey locust provides shade, and the pulp found in its pods is high in protein; it can even be ground up into a flour. Tipu and mulberry trees also offer shade to the more delicate species that grow underneath them. Jones’ mulberries are uncommonly large — and a surprisingly sweet treat for humans and chickens alike. Walking around the corner, Jones leans over a nearby chicken enclosure and grabs a branch. As he shakes it, mulberries rain down. “Chickens are fed!” he laughs. Inside the enclosure, he turns over a eucalyptus log, part of a tree cut from the property. The dirt underneath is dark, rich, fragrant — and absolutely crawling with sowbugs, which just happen to be a delicacy for chickens.

Jones explained the simple science of attracting this so-called pest to his coops. He places some food scraps onto moistened soil, then tops it with a log. After a few days, an explosion of rollie-pollies provides a feast for the hens. The sowbug exoskeletons also provide the added benefit of strengthening his chickens’ eggs shells.

And, like a magician, Jones has turned bugs into breakfast.

The residents at Jones’ ranch — human and barnyard critters alike — eat pretty darn well, and not just at breakfast. They harvest a surprisingly diverse array of goodies, including plums, pecans, hazelnuts, passionfruit, persimmons, artichokes, cherimoyas, pomegranates, jujubes, swiss chard, onions, cabbage, apples, chestnuts, and dozens more.

“The chestnuts have a 500-year productive life,” Jones points out, “and they’re related to oaks, so I knew they would grow well here.”

The other plants and trees on the ranch, of course, also serve an important purpose. Although it’s not native, eucalyptus trees grow fast and provide quality lumber, woodchips, fence posts, and food for goats. Native mulefat offers a fuzzy flower that is great for for starting fires, and it also helps stabilize the creekbed.

Southeast of the creekbed, a portable electric fence keeps the pigs in a shady area under a small grove of oaks. Jones and his team raise them seasonally, then send them out for processing — which they pay for, conveniently, by sharing the meat with the processing company.

The residents of the ranch — and there are between 3 and 6 at any given time — pay just $20 per week for food. The rest is harvested just steps from their beds. Of course, they all put in time working on the ranch — tending the food forest, drilling post holes, fishing, milking the dairy goats, feeding the pigs, etc.

Food for the livestock not only comes from the ranch itself, but from area stores, restaurants, and some unexpected places, too. Produce that’s no longer good enough for sale for humans often ends up in landfills; but why throw out what can be used to feed the livestock? Same goes with slightly stale bread from area bakeries. And those carob pods making a mess in a public parking lot can be raked up and fed to the goats.

As Jones puts it, “There are missed yields everywhere.”

This is his vision for the future: all balance, no waste. Just as it is in nature. He’s beginning to share his work with the community through workshops and through collaborative projects with the county of Ventura. You can see one of these projects in action just south of Woodland Avenue, along the Ojai Valley Trail. Between rows of houses and Highway 33, woodchips cover the hard-packed dirt and 25 young oak trees, planted by volunteers from the local Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints. Jones brought the idea to the Ventura County Board of Supervisors, which — after years of outcry from the public — had been seeking a viable alternative to spraying herbicides like glyphosate.

“Connor brings a positive approach to addressing controversial issues,” says Supervisor Steve Bennett, whose district includes the Ojai Valley. After hearing Jones’ ideas, the county decided to give it a try. “The Ojai (Valley) Trail is a precious asset,” Bennett says. “Our primary focus is to get the weeds under control, then expand the program … Connor offers practical solutions, manageable solutions.”

As Jones’ theory goes, once the oak trees are established, they’ll shade the ground. When paired with the mulch, they will help the soil retain water and discourage weeds from growing. Weeds, despite their bad reputation, do serve a purpose. Puncture vines (also known as goat heads) do pop bicycle tires and are painful when stepped on; hence the County’s eagerness to keep them off the Ojai Valley Trail. But puncture vines’ tap roots break up hard-packed soil, and because they spread out, they shade the dirt and keep it cooler; their purpose is to help heal the soil. So, by creating an environment that is inhospitable to such weeds, one can avoid having to spray herbicides to begin with.

While it’s still a bit too soon to know if the project has longterm viability, it’s got promise, and County staff are receptive to expanding the project to other portions of the trail, Bennett says.

In this grave water crisis, Connor’s work “is the wave of the future,” as Bennett puts it. “We need prophets like Connor to herald the way, and to show us the way … He shows there’s still potential for a great quality of life — just with a different-looking landscape and water use approach.”

Leave A Comment