OFF THE SHELF | Kit Stolz

The Uses of Irreverence

Franz Lidz with his grandson Cloudy.

Franz Lidz first ran away from home at the age of seven. He had a reason: his beloved mother had just gone into the hospital for cancer treatments. Franz missed her terribly and wasn’t sure that his father, a wise-cracking engineer and inventor, really cared all that much about him.

He was a desperate little boy, striking out on his own. He had no idea where he was going but he was utterly determined to get there.

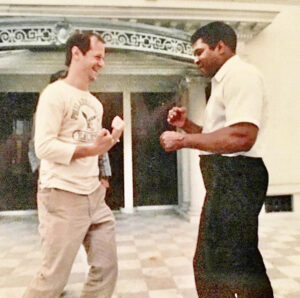

Sixty or so years later, Franz Lidz has grown up to become a reporter and writer, able to get a good story out of nearly anyone, from the town drunk to Muhammed Ali to the Coen brothers to his four crazy uncles. Besides publishing a memoir, a New York character study, and a golf book, Lidz has long reported for or contributed to an unusual variety of major media publications, from the New York Times to Sports Illustrated to Smithsonian (and many others).

It’s a rare skill, to be a generalist in top-flight reporting, and Lidz has an unusual ability to write involvingly on a wide range of subjects, including surprising science (of sourdough, blobfish, or a myriad of other research topics) to unusual sports (such as chess) to interviews with stars. He’s chased the popular artist Leroy Neiman from city to city, finally tracking him down at a coffee shop at Caesar’s Palace in Las Vegas, where they encountered the infamous boxing promoter Don King, who on the spot improvised an ode to Neiman so eloquent — even including a Shakespeare quote — that Lidz put the whole paragraph in the story. Last year Lidz traveled to Italy for the

to explore the invention and evolution of pizza, living in its original home in Naples for a time with his wife Maggie, to delve into a city of thousands of pizzerias and the underground of superstar chefs.

Franz Lidz and Muhammed Ali

He’s profiled sumo wrestlers, covered pigeon races, Jeopardy winners, and countless others, and he can confront as well as amuse. One profile for Sports Illustrated revealed Donald Sterling, the late Clippers owner, as tightfisted and abusive, even to his children. In 2008, Lidz won a “Scoop of the Year” award for a revealing portrait of Yankees owner Steinbrenner, who had sadly fallen into the shadowland of dementia, a secret that had been kept from the public.

Sitting in his flowery backyard in the East End, listening to him think out loud about the range of people and topics he’s written about, one begins to think that his ability to interview has more to do with an innate curiosity than any personal ambition. He is the perhaps the most anonymous quasi-famous person you will ever meet. From whence came this curiosity about people?

Back in suburban Long Island, in 1959, he announced his plan to his father.

“I’m running away,” seven-year-old Franz said. “I mean it.”

Lidz tells this true story in his unique memoir of his youth, “Unstrung Heroes,” a tale of family love and childish heartbreak written in tribute to his “impossible” uncles from New York City.

“Wait!” his father said.

Young Franz looked up hopefully. Perhaps his father was worried about him and wanted him to stay?

“I’ll get my movie camera,” his father said, and went to fetch his Super-8.

Years later the two of them watched the footage from that day. Little Franz, a stereotypical hobo sack on a stick over his little shoulder, wearing a too-large fedora borrowed from one of his uncles, walks out the door and down the walk, receding into the distance. As he diminishes in size, the grown-up Franz sees the scene through the eyes of his father, watching his kid walk away.

“I feel this mournfulness for us both,” Franz Lidz writes of this moment. In a brisk style, seemingly driven by his own boyish enthusiasm, Lidz shows how his wild,irrepressible, and not-a-little-crazy uncles helped him survive a childhood scarred by hard and lonely times.

“My uncles were smelly, screwy, astonishingly scrawny old guys who had abandoned everyday life,” wrote Lidz. “They lived outside the mainstream, but they were happy to be outsiders. They never had to make the same compromises true adults did: they remained innocent and faithful to their own loopy dreams.”

Lidz’s father was financially successful, unlike his four brothers, but they refused to take his “cold, scientific detachment” seriously, teasing him as only brothers can. This dynamic became a family joke that his son treasured. “As a boy, I happily enlisted in their conspiracy against sanity,” he writes. “Now, as I write about these flickering men, I realize they kept me reasonably sane.”

The 1991 book — written early in Lidz’ career as a journalist — balances heartbreak and hilarity with balletic skill. So favorably-reviewed and well-liked was the book that in 1995, Franz’s childhood became the basis for a movie adaptation, directed by Diane Keaton, starring John Turturro as his father, Andie McDowell as his mother, Michael Richards as his paranoid Uncle Danny, and Maury Chaykin as his packrat Uncle Arthur.

Unstrung Heroes film poster

“Unstrung Heroes” drew a 74 percent approval rating from Rotten Tomatoes, and helped the Lidz family buy a farm outside Philadelphia, which the grown-up Franz and his outgoing partner Maggie Lidz stocked with two ebullient daughters and a large menagerie of animals. Lidz didn’t (and still doesn’t) want to complain about the experience of seeing his book adapted into a movie that many people liked and still like, but he makes clear that he much prefers his version. After all, it was his childhood.

He let fly with the one-liners. During production, he saw the screenplay. When asked what he thought, he said that it was “very neatly typed.” Later, New York magazine profiled Lidz, and inquired as to his opinion of the movie.

“My initial fear was that Disney would turn my uncles into Grumpy and Dopey,” he said. “I never imagined that my life could be turned into Old Yeller.” As someone who witnessed his mother’s long descent into mortality, knowing from first-hand experience that cancer sufferers in pain can be more “sullen and bad-tempered” than saintly, he had little patience with Hollywood schmaltz. Spend a little time with Lidz and one realizes that his welcoming presence and amused outlook cloak a sharp wit that can emerge, with a little prodding, like a switchblade from a back pocket.

Lidz thinks he knows what happened to bring out his edge. After his mother’s death, while he was away on a summer school trip across the country after the eighth grade, he came home to an unhappy surprise. His father took him and his kid sister Sandy to meet “someone you’ll really like.” This turned out to be his Shirley, his future stepmother. Lidz looked at her.

“Everything about Shirley — her blouse, her makeup, her boxy orthopedic shoes — was the exact same shade of iron gray,” he wrote. “Everything except her skirt, which was gunmetal. Her face was taut and uninviting. Her smile was as fixed and severe as her hair.”

Despite her steely nature, his father — a fast-talker, an admirer of Spinoza, and relentless punster — abruptly married Shirley and moved his two stunned children and their confused dog in with her and her three obedient children, putting the whole family under her thumb. Franz never liked Shirley and could not find a way to deal with her presence until — inspired by his crazy Uncle Harry, who insisted despite a total lack of evidence that he was an undefeated amateur boxer of great renown — Franz stopped respecting her parental authority.

On a whim at school Lidz changed his first name from Stephen to Franz (in tribute to the composer whose last name he almost shared — Lizst). Shirley hated it. Franz didn’t care a bit. With his new name came almost miraculously a new “uncle-ized” character who, he found, could fearlessly take on his stepmother. He became “open, expansive, scornful … the unflappable Franz Lidz.”

In conversation now Lidz sees this unhappy twist of fate as an inflection point, and the moment in which the skepticism that has become fundamental to his nature and his journalism took root.

“I had complete trust in my father at that time,” he says now. “I felt a sense of betrayal that in a way carried over into the rest of my life. I think I was totally innocent, and it never occurred to me that my father would in a way kind of trick me into meeting this woman and then immediately announce that they were getting married.”

Franz briefly contemplated running away again. “I had been a really good student until my mother’s death. I made the Honor Roll and made her very proud, but after her sudden death I lost all interest in studying and just sort of drifted through college,” he says, looking back. “I wasn’t bitter, but I had no self-esteem and no drive, I just sort of drifted along like a balloon. I never took well to people saying I had to get a job — I never even considered that stuff.”

He transferred from one college to a laxer one, “majoring in sarcasm and minoring in theater,” as he says in his memoir. He thought in a casual way of becoming an actor, but he enjoyed his own antics too much to take the pursuit very seriously. Girls saw him as a romantic lead: he preferred the role of comic relief. He auditioned for the part of the tragic hero Othello dressed as a housepainter, in overalls and a paint-splattered cap. The director looked puzzled.

“I wanted to play Othello not as a noble Moor, but as Benjamin Moore,” explained Lidz. He didn’t get the part. Shortly after graduating, he wrote the owner of the Yankees, George Steinbrenner, offering his services as a crack public relations man, promising to bring “a flamboyant wit, flashing charm, and a killer instinct” to the job. Steinbrenner wrote back, appreciating the line, but said he didn’t have a position. Lidz took a job driving a small town bus. Others might have been disappointed, but Lidz saw it as a perfect opportunity to learn his lines for auditions, which he practiced out loud as he drove.

One afternoon — as he recounted not long ago in “O” magazine — while he was reciting lines for a production of an absurdist Ionescu classic, a dark-haired girl, a high school senior, swung on to the bus with what he describes as an easy grace. Twenty-five cents was the fare: she was a quarter short.

“I prefer a bird in the bush to a sparrow in a barrow,” Lidz said. “The car goes very fast, but the cook beats batter better.”

“What are you talking about?” asked the girl he came to know as Maggie. Lidz recited some more theatrical craziness.

“Is that your idea of a pickup line?” said Maggie.

“It’s Ionescu,” said Lidz.

“It’s corny,” said Maggie.

“Corny?” said Lidz. But he let her ride for free.

Maggie was seventeen: Franz was twenty-four. Despite his lack of prospects and her father’s grave doubts, they married the day after she graduated high school. She proposed, Franz says. She doesn’t remember that now.

“We were young. You don’t really think of anything,” Maggie said with a laugh. “We were very much in love but I was probably an idiot. I don’t think we did anything better than anyone else — we just managed to stay together despite being broke and having everyone against us.”

Maggie went on to become a photo researcher for Rolling Stone and a museum historian: Franz — inspired by a journalistic mentor who preached the importance of being entertaining and, if possible, funny — dropped out of journalism school, took a job with a small paper in Maine and launched a provocative column he called “Sketches and Exasperations.” His first column focused on the town drunk. Forty-three years later, he can still remember its lede.

“It’s 10 in the morning in the Wolves Social Club and Mickey McAleney is telling his third glass of whiskey the story of how the cops had finally nabbed him for murder.

“I was minding my own business on a park bench when, suddenly, I was surrounded by two state troopers and two sheriffs. It was hot as hell. ‘We want you,’ they says. ‘You’re a killer.’ I tell them they’re crazy and they says, ‘No, sir, we’ve got 40 witnesses. You’ve been killing time all morning.’”

Lidz’ talent for irreverent reporting has taken him on assignment all around the world. He has come with Maggie to Ojai in large part to be closer to his grown children. He likes the town, is proud to have planted with two lemon trees out front of the house, a longtime wish of Maggie’s, and he intends to keep at reporting, no matter how many morning deadlines that means. For him, irreverence is not simply “color” but a practical necessity.

“To be funny is in a way just to keep my own interest,” he says. “I have trouble reading straight science writing or just about anything straight through, without a sense of humor — I think it’s hugely important.”

Since the pandemic hit, his daughter Daisy and son-in-law Thor have been sheltering in place with Franz and Maggie, and Franz has been taking long walks with one-and-a-half-year-old grandson Claudius, aka Cloudy, in the mornings.

“Every morning Cloudy and I take a two-hour stroll through Ojai,” Lidz says. “I mostly listen as he talks about his hopes, his dreams, his career aspirations. At this point in his life, he’d like to drive a garbage truck, which he calls an “umph” after the sound it makes while ingesting our trash.”

Leave A Comment